In the prior post, I reviewed the concept of overstuffing – a limited volume with an excessive volume of stuff put in it.

Once more, it is emphasized that in anatomic shoulder arthroplasty, the volume available in the shoulder joint is not the “premorbid” volume, but rather the volume available at surgery after the osteophytes have been removed and after the soft tissue releases have been carried out. Attempting to restore premorbid anatomy to a shoulder with diminished volume will predictably cause a tight shoulder.

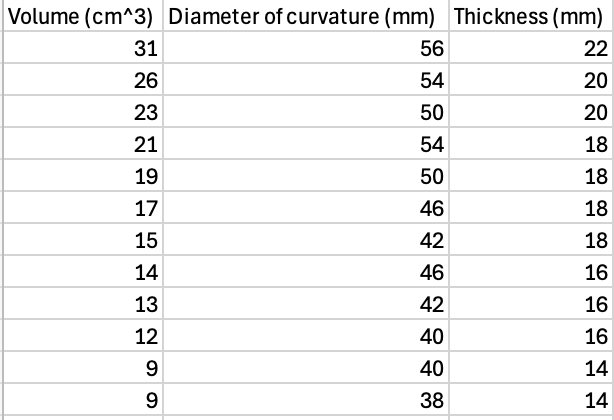

The volume of the components put into this space relates in part to the volume of the implants themselves (the chart below shows the humeral head volume in relation to the diameter of curvature and the thickness of the humeral head in a typical arthroplasty system)

but also to the position in which the component is placed. Shown below is overstuffing related to an insufficient humeral neck cut (red = actual, green = desired).

The preponderance of these articles proposed the importance of two-dimensional radiographs to assess postoperative humeral positioning in relation to “premorbild” anatomy, failing to recognize that overstuffing is a three-dimensioinal issue related to the relationship of the intraoperative volume of the glenohumeral joint and the volume of the components added to this space.

However, one article pointed out that “anatomic’ reconstruction is less important than good postoperative glenohumeral kinematics. It needs to be read by surgeons performing shoulder arthroplasty.

While the volume of the glenohumeral joing cannot be directly measured at surgery, the adequacy of the joint volume for a given set of trial implants can be inferred from the range of glenohumeral motion

Here are the rest of the articles that focus on two-dimensional restoration of the “premorbid anatomy”.

The Shoulder is a Three-Dimensional Structure

Montlake

2024