Identification of distinct tissue niches in RA synovium

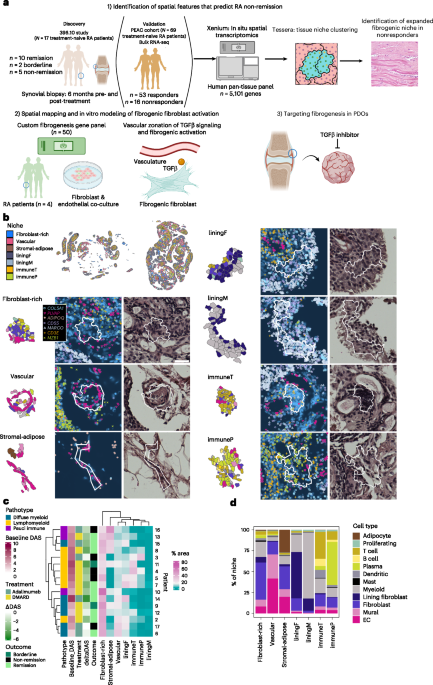

To identify spatial features associated with non-remission, we performed spatial transcriptomics analysis on 17 treatment-naive biopsy samples from patients with early RA as part of the 396.10 study (Fig. 1a). Newly diagnosed RA patients were assigned to triple-therapy disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or anti-tumor necrosis factor biologic adalimumab. Remission, defined as Disease Activity Score-28 for Rheumatoid Arthritis with Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (DAS28-ESR) < 2.6 and Disease Activity Score-28 for Rheumatoid Arthritis with C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) < 2.4, was recorded after 6 months of treatment (Supplementary Table 1). In this cohort, 10 patients achieved remission, 5 did not achieve remission and 2 patients, classified as borderline, met the criteria for only one of either DAS28-ESR or DAS28-CRP remission. Baseline DAS28-ESR/CRP and its individual components did not differ significantly between patients who achieved remission (n = 10) and those who did not (n = 5), but non-remitting patients had significantly lower improvements in disease activity (Supplementary Table 1). We first identified major synovial tissue niches in baseline biopsy samples using a method that leverages spatial differences in transcript expression to draw boundaries between tissue compartments23 (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Graph-based clustering of tiles revealed seven niches that were enriched for distinct transcripts and their corresponding cell types: (1) fibroblast-rich, (2) vascular, (3) stromal-adipose, (4) lining fibroblasts (‘liningF’), (5) lining macrophages (‘liningM’), (6) T cells and B cells (‘immuneT’) and (7) plasma cells (‘immuneP’; Fig. 1c,d, Extended Data Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Table 1). The lining niches (liningF, liningM) consisted of a mix of synovial lining fibroblasts (CD55+) and lining macrophages (HTRA1+). The immune niches contained dense infiltrates composed of either primarily T cells (CD3E+) and B cells (MS4A1+; ‘immuneT’) or plasma cell aggregates (MZB1+; ‘immuneP’). Vascular niches consisted of various endothelial subtypes including venules (SELP+), capillaries (PLVAP+) and arterioles (PODXL+), mural cells, including pericytes (RGS5+) and vascular smooth cells (ACTA2+) and NOTCH3+ vascular fibroblasts. Stromal-adipose niches contained vascular cells and fibroblasts embedded among adipocytes (ADIPOQ+). Fibroblast-rich niches were composed primarily of sublining fibroblasts (COL6A1hi).

a, Schematic overview of the study. b, Visualization of niches in a single synovial biopsy sample. Representative examples for each individual niche type with component cell types labeled are shown with corresponding DAPI and H&E images. Scale bar, 50 µm. c, Heat map representing the abundance of tissue niches, by tissue area, in each treatment-naive biopsy and the associated clinical metadata. Baseline DAS and ΔDAS represent the DAS28-ESR pretreatment and the change at 6 months, respectively. d, Stacked bar plot representing the proportion of cell types per niche. Schematic in a was created with BioRender.com.

Source data

Hierarchical clustering of niche composition classified samples into three broad categories, one characterized by stromal-adipose enrichment (n = 4), another by immune niche enrichment (n = 5) and a third marked by expanded vascular and fibroblast niches (n = 7; Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1d). While we observed high concordance between immune niche tissue area and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-based lymphomyeloid pathotype classification24 (Extended Data Fig. 1e), clear distinctions did not appear between the diffuse myeloid and pauci-immune pathotypes (Fig. 1c), suggesting that spatial transcriptomics analysis captures complexity in cellular organization beyond traditional histologic assessment of synovial tissue pathotype. Tissue areas of fibroblast-rich niches negatively correlated with the area of combined immune niches, consistent with prior studies utilizing histology25,26 and single-cell transcriptomics11,15,16 (Extended Data Fig. 1f). We observed no significant differences in baseline niche composition by remission status, although we could not exclude the possibility that heterogeneity in tissue sampling masked underlying distinctions (Extended Data Fig. 1g). Therefore, we investigated whether transcriptional differences could differentiate remission groups.

Elevated fibrogenic signatures in non-remission

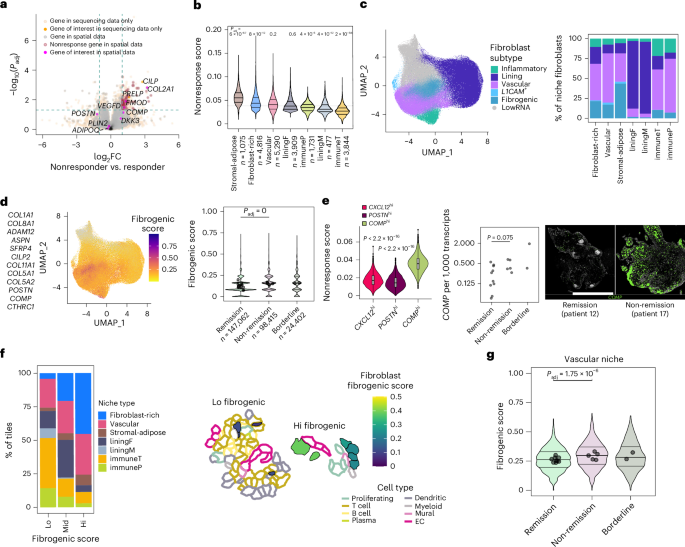

Since the sample size of our cohort was limited, we leveraged bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data from the larger PEAC cohort (n = 69)16 to identify genes significantly associated with nonresponse (Fig. 2a). We applied the nonresponder gene signature to spatial niches and found enrichment of the signature in stromal-adipose, fibroblast-rich and vascular niches (Fig. 2b). Among synovial cell types, fibroblasts were enriched in the three nonresponder-associated niches and exhibited the highest nonresponse scores (Extended Data Fig. 2a).

a, Volcano plot representing differentially expressed genes in nonresponders versus responders from bulk RNA-seq analysis of synovial tissue derived from treatment-naive patients. Genes in the upper-right quadrant are log2 fold change > 1 and Padj < 0.05 between nonresponders and responders. Differential expression was tested with DESeq2 (negative-binomial generalized linear model (GLM); Wald test); P values are false discovery rate (FDR) corrected. Selected genes, including those in the nonresponder gene set, are highlighted. b, Violin plot representing the distribution of nonresponse scores per niche type, with the number of niches analyzed indicated. Statistical comparison by two-sided Wilcoxon test comparing a downsampled selection of nonresponse scores in 500 niches from each niche type to a random selection of scores from 500 other niches, with Bonferroni correction. Horizontal line represents the median nonresponse score across all niches analyzed. c, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot of fibroblasts annotated by subtype, and stacked bar plot representing the proportion of each fibroblast subtype within each niche. d, UMAP (left) and violin plot (right) displaying the projection and distribution of single-cell fibrogenic U cell scores, respectively. Each dot in the violin plot represents the median fibrogenic score per patient, with signature genes indicated to the left of the UMAP. Statistical comparison by quasibinomial GLM with patient included as a cofactor, with Bonferroni correction across cell types. e, Violin plot (left) displaying the distribution of the nonresponder signatures (n = 290 genes) in COMPhi, POSTNhi and CXCL12hi clusters, as calculated by UCell. Two-sided Wilcoxon test was used for statistical comparisons between the groups (P < 2.2 × 10−16 between COMPhi nonresponse score and each cluster). Jitter plot (right) representing quantification of normalized COMP transcript expression at baseline by remission status, with representative images of COMP transcript expression. Scale bar, 2 mm. Statistical comparison by two-sided Wilcoxon test. f, Stacked bar plot (left) representing the proportion of each niche type that had fibrogenic scores in the low (‘lo’), medium (‘mid’) and high (‘hi’) categories with a representative example (right) of niche tiles that scored low and high for fibrogenic scores. g, Violin plot representing the distribution of fibrogenic scores for vascular niche tiles by remission status. Each dot represents the median per-patient fibrogenic score in vascular niches. Statistics calculated by two-sided GLM with patient as a cofactor, with FDR correction across niche types. The box plot in e shows the median and 25th–75th percentiles, the whiskers represent 1.5 times the interquartile range, and outliers are shown beyond the whiskers.

To identify specific fibroblast phenotypes15 most strongly associated with nonresponse, we subtyped fibroblasts in our spatial transcriptomic data and identified one lining and four sublining subsets. The fibrogenic sublining subset was characterized by high ECM gene expression (COL6A1, COL8A1, COMP), the inflammatory subset by expression of inflammatory mediators (CXCL12), and the vascular subset by NOTCH3 and THY1 expression. A minor subpopulation was marked by expression of L1CAM, a nerve-associated adhesion molecule27 (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2b). We confirmed that lining fibroblasts were the most abundant fibroblast subtype in lining niches and that vascular and inflammatory fibroblasts were most enriched in the immune niches (Fig. 2c)28. Notably, fibrogenic fibroblasts were the subtype most enriched for the nonresponse signature (Extended Data Fig. 2c) and were specifically expanded in the nonresponse-associated fibroblast-rich, stromal-adipose and vascular niches (Fig. 2c).

To assess whether fibrogenic programs stratified remission groups, we calculated a 12-gene fibrogenic activation score using fibrogenic fibroblast markers, including POSTN, CTHRC1 and SFRP4 previously described in fibrotic disease29,30,31 (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 2d). The fibrogenic score was significantly elevated in pretreatment fibroblasts of non-remitting patients compared to remitting patients (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 2e,f).

While the vascular and inflammatory fibroblast compartments have previously been characterized8,9,12,14, the fibrogenic compartment in RA remains incompletely understood25. To assess the phenotypic overlap between RA fibrogenic fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in fibrotic diseases, we first confirmed enrichment of the 12-gene fibrogenic fibroblast signature in publicly available systemic sclerosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis datasets32,33 (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). Spatial profiling of RA synovial tissue and lung tissue from patients with late-stage RA interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) exhibiting usual interstitial pneumonia (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d) then revealed high and specific enrichment of the signature in regions identified through histology as subepithelial-localized fibroblastic foci (Extended Data Fig. 3c). In RA synovial tissue, the fibrogenic signature was expressed more diffusely throughout the sublining compartment, with high-expressing regions characterized by deeper pink eosin staining compared to low-expressing regions, indicating increased ECM deposition. Collectively, we observed strong transcriptomic overlap between fibrogenic populations in RA and fibrotic disease (Extended Data Fig. 3d).

Next, to determine whether there are specific cellular subtypes within the RA fibrogenic compartment associated with nonresponse, we subsetted and reclustered fibroblasts from patients in the AMP RA/SLE single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset15 that were highly enriched for the 12-gene fibrogenic signature derived from the spatial transcriptomic dataset (top 10% of cells; Extended Data Fig. 4a). We observed three broad fibrogenic subclusters: a CXCL12-expressing inflammatory cluster, a COMP-expressing cluster that coexpressed DKK3 and FMOD, previously found to be associated with treatment resistance17, and a POSTN-expressing cluster relatively enriched for COL1A1 expression, illustrating distinct phenotypes among RA fibrogenic fibroblasts (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Genes coexpressed in the POSTNhi cluster were positively associated with treatment response in the PEAC bulk RNA-seq data, in contrast to COMP-coexpressed genes, which were more associated with treatment nonresponse (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). Accordingly, the COMPhi fibroblast cluster exhibited striking enrichment of the nonresponder signature compared to the POSTNhi and CXCL12hi fibrogenic subclusters, suggesting that COMP expression, specifically denotes the subset of fibrogenic fibroblasts in RA associated with treatment resistance33,34 (Fig. 2e). At the transcript level, COMP was more elevated in the treatment-naive biopsy samples of patients who failed to achieve remission compared to DKK3, FMOD or POSTN (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 4e) and was more broadly enriched across non-remission niches (Extended Data Fig. 4f). Additionally, baseline COMP+ cell abundance correlated with reduced 6-month and 12-month improvements in tender joint counts (deltaTJC28) in the non-remission group (Extended Data Fig. 4g). Further, there was a positive trend among the remission and non-remission groups between baseline COMP+ cell abundance and DAS28-ESR at 12 months, highlighting the link between COMP+ cell abundance and longer-term disease activity (Extended Data Fig. 4g).

Next, to investigate tissue niches in which increased fibrogenic activation might drive differences in remission status, we first classified all niche tiles into low, medium and high for fibrogenic signature expression (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 4h). Immune and lining niches were highly represented among tiles with low and medium fibrogenic expression, whereas fibroblast-rich, stromal-adipose and vascular tiles were prominently represented among tiles with high fibrogenic signatures, consistent with nonresponder signature enrichment. Among the three relevant niches, fibrogenic scores in only the vascular niche were elevated in non-remission, suggesting that vascular-associated fibrogenic activity may drive treatment nonresponse (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 4i).

Perivascular compartmentalization of TGFβ signaling

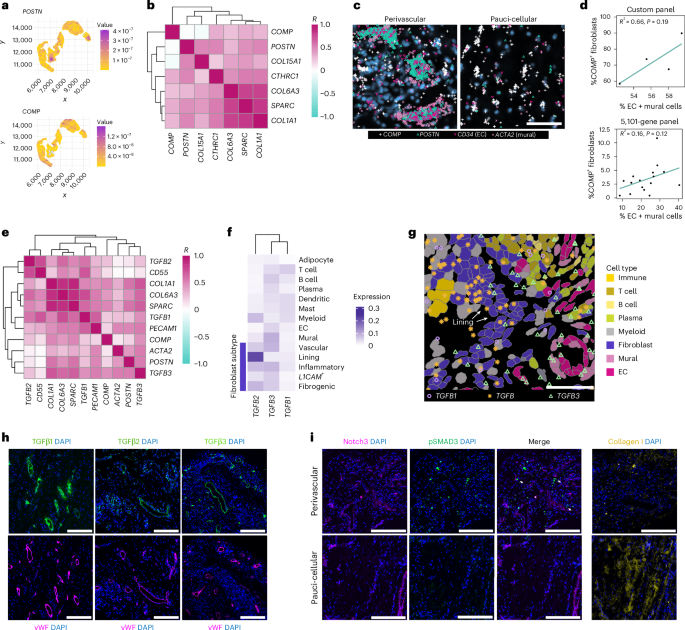

To improve localization of fibrogenic fibroblasts in synovial tissue, we designed a targeted panel of 50 stromal-associated genes for spatial transcriptomics analysis of additional RA synovial tissue samples (n = 4). The smaller panel enhanced the detection of relevant transcripts, including TGFβ isoforms, key regulators of fibrosis19 and COMP (~14-fold increased detection). Gating on fibrogenic tissue regions, defined by high COL1A1 expression, we found that COMP and POSTN transcript kernel density estimates mapped to spatially distinct areas (Fig. 3a,b), consistent with their differential single-cell expression patterns15. We observed two major patterns of COMPhi fibroblast localization: (1) within pauci-cellular fibroblast-rich regions and (2) within the distal layers of perivascular regions, surrounding mural cells and vascular fibroblasts (Fig. 3c). Accordingly, patient-level analysis of the spatial data revealed a positive association between the proportion of vascular cells and the abundance of COMP-expressing fibroblasts (Fig. 3d). POSTN transcripts, in contrast, were coexpressed with mural cell (ACTA2) and vascular fibroblast (COL15A1) markers, indicating strong expression of POSTN in the proximal cell layers of vascular regions (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Together, our data indicate that both subsets of fibrogenic fibroblasts localize to the perivascular compartment in RA synovia, but in distinct layers.

a, Visualization of kernel density estimates of POSTN (top) and COMP (bottom) expression within a representative COL1A1-high region. b, Heat map showing mean pixel correlations across synovial samples (n = 4) between kernel densities for selected fibrogenic genes within COL1A1-high regions. c, Representative examples (n = 4 RA tissues) of COMP transcript expression in perivascular and pauci-cellular regions. Scale bar, 50 µm. d, Correlation between the percentage of fibroblasts that express COMP (count > 0) per sample and abundance of endothelial and mural cells as a percentage of total cells in the same sample. Statistics calculated by two-sided Pearson’s correlation coefficient test. Top: 4 samples analyzed with a 50-gene custom panel. Bottom: 16 samples analyzed with a 5,101-gene panel. e, Mean pixel correlations across samples (n = 4) for TGFB isoform expression compared to selected fibroblast and endothelial markers. f, Heat map representing relative expression of TGFB isoforms across different cell types in synovial samples (n = 17) analyzed with a 5,101-gene panel. g, Example of data in f showing TGFB transcripts overlaid on cell types. Scale bar, 50 µm. h, Immunofluorescence staining of RA synovial tissue showing protein expression of TGFβ isoforms relative to EC marker vWF. TGFβ3 and vWF staining were performed on serial sections. i, Immunofluorescence data showing Notch3, Collagen 1 and pSMAD3 staining in perivascular and pauci-cellular regions of the RA synovium. Scale bars, 200 µm. Immunofluorescence is representative of n > 5 RA synovial tissue.

We next asked whether TGFβ isoform expression is spatially associated with fibrogenic niches in RA (Fig. 3e). TGFB1 colocalized with the lining fibroblast marker CD55 and endothelial cell (EC) marker PECAM1. TGFB2 transcripts strongly colocalized with CD55. TGFB3 transcripts not only colocalized with markers of endothelial (PECAM1) and mural (ACTA2) cells, suggesting vascular and perivascular enrichment, but also overlapped with fibrogenic transcripts, including POSTN, COMP and COL1A1, indicating broad coexpression within fibrogenic populations. Analysis of TGFβ isoform expression by cell type in 396.10 spatial transcriptomic data confirmed lining fibroblast-specific expression of TGFB2, diffuse expression of TGFB1 and stromal-vascular-enriched TGFB3 expression (Fig. 3f,g and Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Immunofluorescence staining of synovial tissue revealed perivascular localization of TGFβ1, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 protein (Fig. 3h), although TGFβ2 also appeared in immune aggregates. Accordingly, we observed that a specific indicator of active TGFβ signaling, pSMAD3, was restricted to fibroblasts in vascular regions and absent in pauci-cellular regions characterized by dense collagen deposition (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. 1c), suggesting that active TGFβ signaling occurs specifically in the vascular compartment. Together, the observed spatial patterning of both fibrogenic gene expression and TGFβ indicates that the perivascular niche is an important hub for fibrogenic signaling.

ECs spatially pattern TGFβ responsiveness

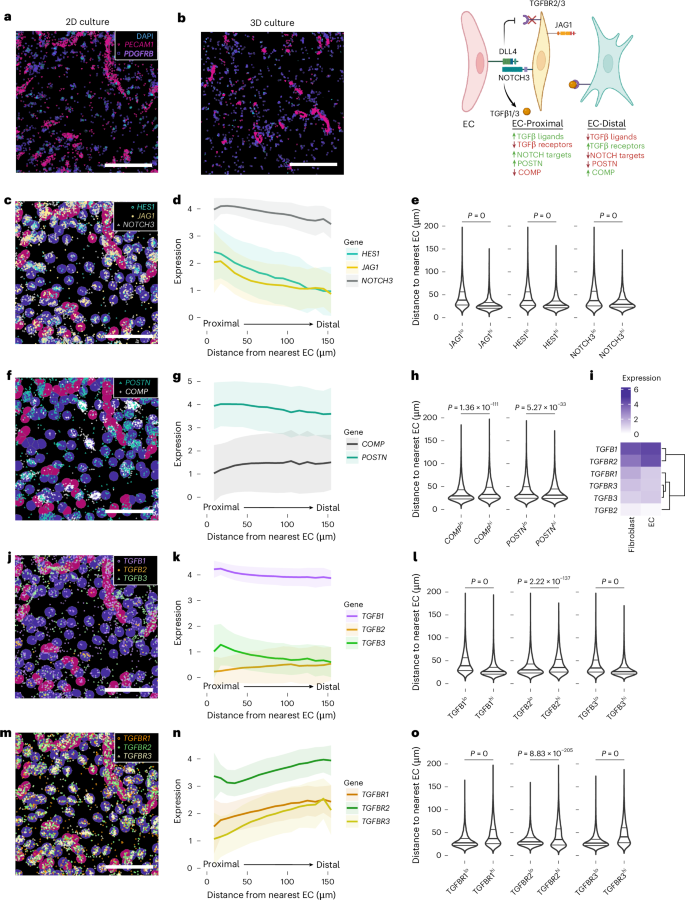

To better understand how vascular ECs generate spatial patterning of TGFβ signaling in fibroblasts, we modeled and spatially profiled co-cultures of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with synovial fibroblasts in two-dimensional (2D) and in three-dimensional (3D) systems (Fig. 4a,b). In both systems, we observed distinct fibroblast transcriptional programs as a function of proximity to the nearest EC: fibroblasts in the most proximal layer expressed Notch target genes including JAG1, HES1 and NOTCH3, which decreased in distal layers of fibroblasts that were over one cell layer away (Fig. 4c–e and Extended Data Fig. 5a–c). Like Notch target genes, POSTN expression was also highest on the proximal layer of fibroblasts adjacent to ECs and gradually decreased in distal fibroblasts, in contrast to COMP expression, which increased in distal compartments (Fig. 4f–h and Extended Data Fig. 5d–f). Collectively, EC-derived signals pattern fibrogenic gene expression in a proximal-to-distal manner, where POSTN represents an EC-proximal program and COMP expression represents an EC-distal program.

a,b, Representative visualization of spatially profiled 2D (a) and 3D (b) co-culture with transcripts for fibroblast marker PDGFRB, and endothelial marker PECAM1, overlaid on DAPI. Schematic summarizing the spatial distribution of fibroblast transcripts based on EC proximity on the right. c,f,j,m, Example images of gene expression distribution overlaid on labeled cell types, to a maximum of randomly selected 1,500 transcripts per gene, with Notch target genes shown in c, fibrogenic markers in f, TGFB ligands in j and TGFB receptors in m. d,g,k,n, Line plots representing average expression of transcripts per fibroblast relative to the EC distance, with Notch target genes shown in d, fibrogenic markers in g, TGFB ligands in k and TGFB receptors in n. Solid line shows the mean; shaded regions show one standard deviation. e,h,l,o, Distance to the nearest EC in the top-versus-bottom quantile of cells by expression of each gene, with Notch target genes shown in e, fibrogenic markers in h, TGFB ligands in l and TGFB receptors in o. Statistics by two-sided Wilcoxon tests comparing distances from ECs for the top-versus-bottom quantiles of cells in expression of each gene. i, Heat map representing expression of TGFB ligands and receptors by cell type in the co-culture. Scale bars, 200 µm (a–c, f, j and m). Schematic in b created with BioRender.com.

Source data

Next, we evaluated the distribution of TGFβ isoforms and their receptors along the EC proximal-to-distal axis to identify receptor–ligand pairs responsible for differential fibroblast responses to TGFβ. Consistent with the expression pattern in RA synovia, TGFB1 was expressed on ECs and on the EC-proximal fibroblast layer, with fewer average transcripts in EC-distal fibroblasts (Fig. 4i–l and Extended Data Fig. 5h–j), while TGFB2 was lowly and diffusely expressed. TGFB3, like TGFB1, was induced on endothelial-proximal fibroblasts and then sharply decreased in EC-distal fibroblasts. Transcripts of TGFBR1, the TGFβ signaling co-receptor, TGFBR2, the ligand-binding receptor, and TGFBR3, a high-affinity TGFβ binding co-receptor for all isoforms35,36, were lowest in EC-proximal layers and gradually increased in EC-distal fibroblasts (Fig. 4m–o and Extended Data Fig. 5k–m); the observations were concordant across both the 2D and 3D culture systems. Collectively, these data suggest that endothelial-derived signals determine spatial patterning of TGFβ signaling via paired regulation of TGFβ ligands and receptors.

Patterning of TGFβ responsiveness via Notch signaling

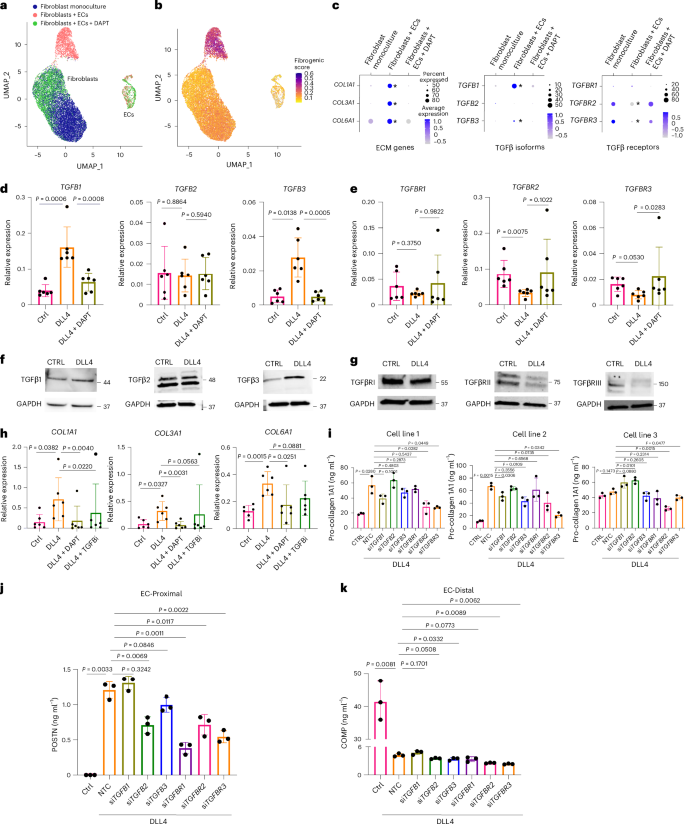

Given the distinct spatial pattern of TGFβ-related transcripts in fibroblasts generated by contact with neighboring ECs, we evaluated the potential role of endothelial-derived Notch in regulating TGFβ signaling. We reanalyzed scRNA-seq data from Matrigel-embedded 3D organoids of fibroblasts and ECs treated with or without the Notch inhibitor DAPT9 (Fig. 5a–c and Extended Data Fig. 6a). We observed significant induction of TGFB1, TGFB3 and fibrogenic gene expression when ECs were included in organoids as well as suppression of TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 expression (Fig. 5c). The addition of DAPT reversed TGFB induction and TGFBR suppression, directly implicating Notch signaling as an upstream regulator of fibroblast TGFβ signaling.

a, UMAP plot of isolated single cells from the indicated 3D co-culture conditions9. Fibroblast monoculture: organoid containing fibroblasts only; Fibroblasts + ECs: organoids containing fibroblasts and ECs; Fibroblasts + ECs + DAPT: organoids containing fibroblasts and ECs treated with a Notch inhibitor. b, UMAP plot of cells from organoid culture shaded by level of fibrogenic gene signature score calculated with UCell. c, Dot plots representing the expression of selected genes by condition. The asterisk indicates genes and conditions with P < 1 × 10−100 between monoculture and co-culture. d,e, RT–qPCR analysis of TGFB isoform (d) and receptor gene expression (e) on unstimulated or DLL4-stimulated fibroblasts treated with or without DAPT (10 µM) for 72 h. f,g, Immunoblots of TGFβ isoforms (f) and receptors (g) with lysates from unstimulated or DLL4-stimulated fibroblasts (72 h). Data are representative of three independent experiments. h, RT–qPCR analysis of COL1A1, COL3A1 and COL6A1 gene expression on unstimulated or DLL4-stimulated fibroblasts treated with or without TGFβ inhibitor (SB431542; 10 µM) or DAPT (10 µM) for 72 h. i, ELISA quantification of fibroblast production of pro-collagen I alpha 1 in 3 cell lines over 24 h after 3 days of treatment with siRNA (20 nM) with or without DLL4 stimulation. j,k, ELISA quantification of fibroblast production of POSTN (j) and COMP (k) over 24 h after 3 days of treatment with siRNA (20 nM) with or without DLL4 stimulation. For d, e and h, each data point represents an independent cell line (n = 6); for i–k, each data point represents biological replicates (n = 3) from a single-cell line and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was performed by a two-sided ratio paired t-test for d, e and h, two-sided Bonferroni-corrected Wilcoxon test for c and unpaired two-sided t-tests for i–k.

A 2D culture system showed similar effects of Notch activation on fibroblast TGFβ signaling. We stimulated synovial fibroblast cell lines (n = 6) with plate-bound DLL4 and observed strong induction of TGFB1 and TGFB3 gene and protein expression and suppression of TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 that was reversed with the addition of DAPT (Fig. 5d–g). Further, there were significant peaks in the promoter regions of TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 for binding of a Notch-associated transcription factor (RBPJ) in HepG2 cells, supporting a role for Notch in direct transcriptional regulation of TGFβ receptors (Extended Data Fig. 6b).

Next, we assessed the impact of Notch and TGFβ signaling on fibrogenic gene expression and observed induction of fibrogenic collagens (COL1A1, COL3A1, COL6A1) with DLL4 stimulation that was reversed with the addition of DAPT or TGFβ inhibitor (SB431542; Fig. 5h). We evaluated the extent to which Notch-mediated TGFβ signaling occurs in a cell contact-dependent or soluble manner (Extended Data Fig. 6c–f). Low concentrations of soluble TGFβ1 were induced in the supernatant of DLL4-stimulated cells (Extended Data Fig. 6c), but conditioned medium from DLL4-stimulated fibroblasts was unable to induce TGFβ-responsive genes in recipient fibroblasts (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Similarly, when we cultured fibroblasts in a Transwell chamber above DLL4-stimulated fibroblasts, we observed no induction of TGFβ signaling (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Additionally, antibody blockade against individual or pan-TGFβ isoforms did not substantially diminish ECM production. Altogether, our findings suggest that Notch-induced TGFβ signaling primarily occurs in a contact-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 6f).

We then systematically tested the effects of each TGFβ isoform and receptor for Notch-mediated fibrogenic signaling (Fig. 5i–k and Extended Data Fig. 6g–i). siRNA knockdown of TGFB diminished pro-collagen 1 alpha 1 (PRO-COL1) production in two of three cell lines for siTGFB1, one of three cell lines for siTGFB2 and one of three cell lines for siTGFB3. Combinatorial knockdown of pairs of TGFβ isoforms (Extended Data Fig. 6h) did not significantly diminish PRO-COL1, suggesting redundant roles for all three TGFβ isoforms in mediating Notch-driven fibrogenic signaling in vitro. Among TGFβ receptors, knockdown of TGFBR1 did not significantly alter pro-collagen production (Extended Data Fig. 6g), whereas TGFBR2 knockdown diminished production in two of three cell lines and TGFBR3 knockdown diminished production in three of three cell lines (Fig. 5i). Combinatorial knockdown of TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 diminished PRO-COL1 production the most, suggesting that expression levels of these receptors more strongly regulate PRO-COL1 compared to TGFBR1 (Extended Data Fig. 6h). Subsequently, we examined how DLL4 stimulation regulated the distinct EC-proximal (POSTN) and EC-distal (COMP) fibrogenic programs (Fig. 5j,k and Extended Data Fig. 6i). Although the production of both proteins was strongly induced by soluble TGFβ (Extended Data Fig. 6f), POSTN was potentiated by Notch signaling, whereas COMP was highly suppressed, and both were diminished with TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 knockdown. Overall, while the responses of COMP and POSTN expression to soluble TGFβ and TGFβ receptor knockdown were similar, opposing impacts of Notch signaling on COMP and POSTN implicated an additional mechanism by which Notch regulates the patterning of TGFβ responsiveness in fibroblasts.

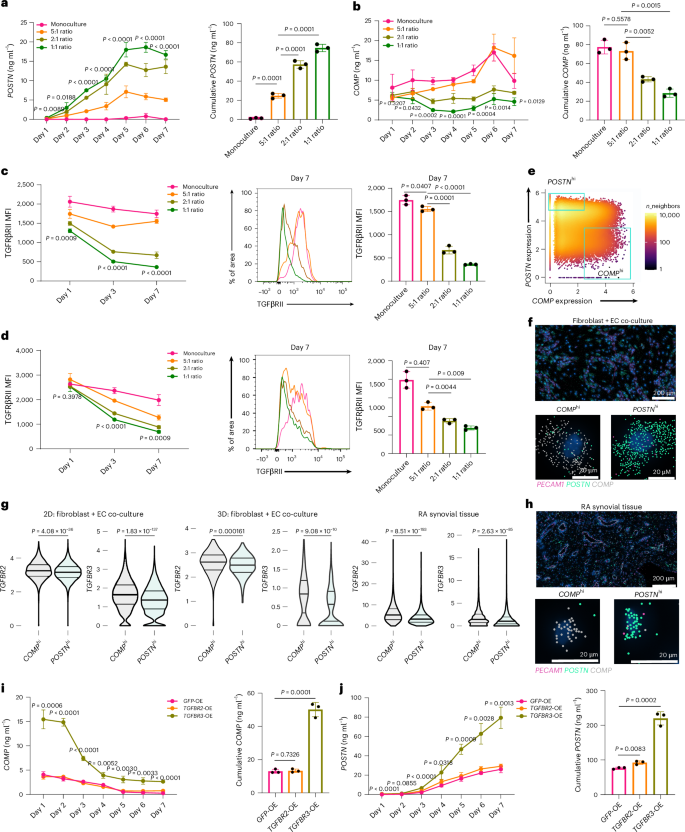

To quantify the temporal dynamics of EC-derived Notch in regulating fibrogenic programs, we first set up 2D and 3D co-cultures treated with or without DAPT and TGFβi, collecting and replacing media every 24 h to measure interval production of POSTN, COMP and PRO-COL1 (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). In both systems, co-cultured fibroblasts exhibited sustained production of PRO-COL1 and POSTN compared to monocultured fibroblasts and was diminished with DAPT or TGFβi. In contrast, COMP production temporally decreased in co-culture, consistent with the suppression of COMP expression by endothelial-derived Notch signaling. Next, we cultured a fixed number of fibroblasts with varying numbers of ECs, measuring interval protein production. In an EC ratio-dependent manner, POSTN production was significantly induced, whereas COMP production was suppressed (Fig. 6a,b). Furthermore, the suppression of COMP production mirrored the temporal EC ratio-dependent downregulation of TGFβRII and TGFβRIII, suggesting that changes in fibroblast TGFβ receptor availability may create a dynamic threshold on the ability of fibroblasts to respond to TGFβ (Fig. 6c,d). Accordingly, analysis of Xenium co-culture and synovial tissue data revealed significantly higher expression of TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 in COMPhi fibroblasts compared to POSTNhi fibroblasts (Fig. 6e–h).

a–d, A fixed number of fibroblasts were seeded with varying numbers of HUVECs. Monoculture: 5,000 fibroblasts, 5:1 ratio: 5,000 fibroblasts and 1,000 HUVECs, 2:1 ratio: 5,000 fibroblasts and 2,500 HUVECs, 1:1 ratio: 5,000 fibroblasts and 5,000 HUVECs. a,b, ELISA quantification of POSTN (a) and COMP (b) production during co-culture. P values in the line graphs are displayed for the comparisons between monoculture and 1:1 ratio. The respective bar charts to the right represent the area under the curve. c,d, Flow cytometric quantification of fibroblast TGFβRII (c) and TGFβRIII (d) at the indicated days during co-culture with ECs. P values are shown for comparisons between monoculture and 1:1 ratio. Representative flow cytometry histograms and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) quantification for day 7 of co-culture are shown. e, Gating strategy for classifying COMPhi and POSTNhi fibroblasts from the Xenium-profiled co-culture (mutually exclusive top quantile of cells expressing each gene, with POSTN ≤ 3.5 for COMPhi). f, Representative examples of COMPhi and POSTNhi fibroblasts in 2D culture are shown with transcripts. g, Violin plot showing the distribution of TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 transcripts on POSTNhi and COMPhi gated fibroblasts in 2D co-culture, 3D co-culture and RA synovium. h, Representative example (n = 4 RA synovial tissue) of gated (mutually exclusive top quantiles of expressing cells) COMPhi and POSTNhi synovial fibroblasts with transcripts. i,j, ELISA quantification of COMP (i) and POSTN (j) production from co-culture of fibroblasts overexpressing (OE) GFP, TGFBR2 or TGFBR3 with ECs in a 1:1 ratio. P values are shown for the comparison between TGFBR3-OE and GFP-OE data points. The bar plot on the right represents the area under the curve. Data points are shown as the mean ± s.d., represent n = 3 biological replicates and are representative of at least two independent experiments. For statistical analysis, a two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for a–d, i and j, and a two-sided Wilcoxon test was used for g.

Next, to determine the extent to which suppression of COMP production in co-culture was mediated by dynamic TGFβ receptor downregulation, we used lentivirus to overexpress TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 in fibroblasts (Fig. 6i,j and Extended Data Fig. 7c). ECs co-cultured with fibroblasts overexpressing TGFBR3, but not TGFBR2, had significantly diminished suppression of COMP. Moreover, daily POSTN production was significantly enhanced in co-cultures with TGFBR3-overexpressing fibroblasts, despite negligible effects of TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 on the fibroblast response to TGFβ itself, suggesting that modulation of TGFβRIII availability is specific to endothelial-derived Notch signaling in patterning of TGFβ responsiveness (Extended Data Fig. 7d,e).

Notch disruption induces fibrogenic activation

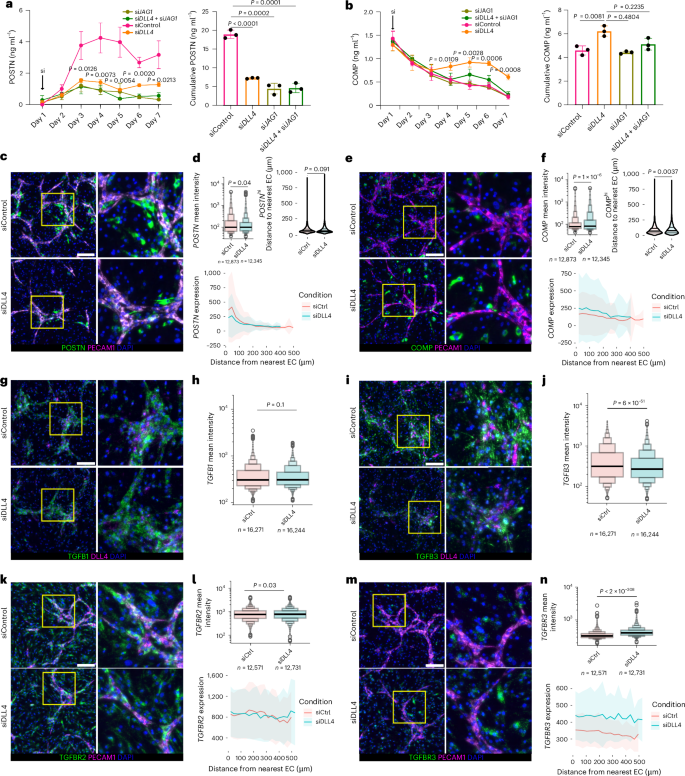

Since we established that steady-state EC-derived Notch signaling generates a proximal-to-distal axis of TGFβ response in fibroblasts, we next sought to understand the consequences of disrupting steady-state patterning on fibrogenic gene expression. We hypothesized that disruption of a steady-state Notch signaling can activate expression of EC-distal gene expression programs. Knockdown of EC-specific Notch ligand DLL4, fibroblast-expressed JAG1 or a combination of both at the start of co-culture significantly diminished POSTN (Fig. 7a,b). COMP was suppressed through day 3 but was de-repressed starting on day 4 in the DLL4 knockdown condition (Fig. 7b).

a,b, ELISA quantification of POSTN (a) and COMP (b) production from fibroblasts and EC co-culture (1:1 ratio) treated with the indicated siRNAs (20 nM). P values are shown for the comparison between DLL4 siRNA and control siRNA conditions (cumulative POSTN P < 0.0001, cumulative COMP P = 0.0081). The bar plots to the right represent the area under the curve. c–n, RNAscope quantification of fibrogenic program in response to Notch perturbation. Representative images of siControl-treated and siRNA against DLL4 (siDLL4)-treated co-cultures with indicated fibrogenic (a–f), TGFB (g–j) and TGFBR (k–n) transcripts shown. PECAM and DLL4 transcripts denote endothelial cells. Scale bars, 200 μm. d,f,h,j,l,n, Boxen plots representing the distribution of MFIs of the corresponding genes in siControl and siDLL4 conditions on the indicated number of cells selected for quantification. d,f,l,n, Ribbon plots showing spatial gene expression patterns in relation to EC proximity for indicated genes between siRNA conditions. Solid line shows the mean intensity, and shaded regions show one standard deviation. d,f, Violin plots showing the distance to the nearest EC (in μm) for POSTNhi and COMPhi cells, defined as cells with the highest quantile of POSTN and COMP fluorescence intensity, respectively. P values for the comparisons between siCtrl and siDLL4 are P < 6 × 10−51 and P < 2 × 10−308 for TGFB3 (j) and TGFBR3 (n), respectively. The data in a and b are shown as means ± s.d., represent n = 3 biological replicates and are representative of at least two independent experiments. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was performed for a and b and two-tailed Wilcoxon tests for d, f, h, g, l and n. In the boxen plots, boxes show nested quantile ranges (median, 25–75%, 12.5–87.5%, 6.25–93.75%, and so on), the center line shows the median (50th percentile), the whiskers represent minimum and maximum values, and the outliers are shown as individual points outside the whiskers.

To characterize alterations in spatial patterning resulting from disruption of steady-state Notch signaling, we applied in situ hybridization to co-cultures treated with control or DLL4 siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 1a). As at the protein level, we observed significant induction of COMP expression (P = 1.4 × 10−6) and diminishment of POSTN expression (P = 0.04) in the DLL4 knockdown condition (Fig. 7c–f). When we compared the average expression of POSTN in relation to EC distance, we observed no significant changes, as expected, given its EC-proximal restricted patterning (Fig. 7c,d). In contrast, we observed that average COMP expression was higher with DLL4 knockdown compared to control and that the average distance of COMPhi cells to ECs increased (Fig. 7e,f). We also examined the effect of DLL4 knockdown on TGFβ isoform and receptor expression (Fig. 7g–n). While we observed no significant changes in the patterns of TGFB1 and only modest changes for TGFBR2 expression across cells (Fig. 7g,h,k,l), we observed a significant increase in the average expression of TGFBR3 and decrease in the average expression of TGFB3 (Fig. 7i,j,m,n). As with COMP expression, we observed elevated TGFBR3 expression in both EC-proximal and EC-distal compartments of DLL4 knockdown co-culture (Fig. 7n). Together, these data suggest that the expansion of COMP-expressing fibroblasts was specifically linked to the de-repression of TGFβRIII mediated by DLL4 knockdown, rather than increases in TGFβ expression, a potential mechanism by which EC-derived Notch signaling dictates the spatial patterning of fibrogenic signaling.

To examine the extent to which COMP expression is linked to Notch-mediated tuning of fibroblast sensitivity in synovial tissue, we scored vascular niches according to their expression of Notch transcriptional targets (Supplementary Fig. 2b). TGFBR3 expression was negatively correlated with vascular Notch activation scores across biopsy samples, supporting the role of Notch signaling in suppressing TGFβ receptor expression in vivo. Collectively, our in vitro and in vivo results suggest that Notch can tune TGFβ sensitivity via TGFβ receptor regulation in vascular niches.

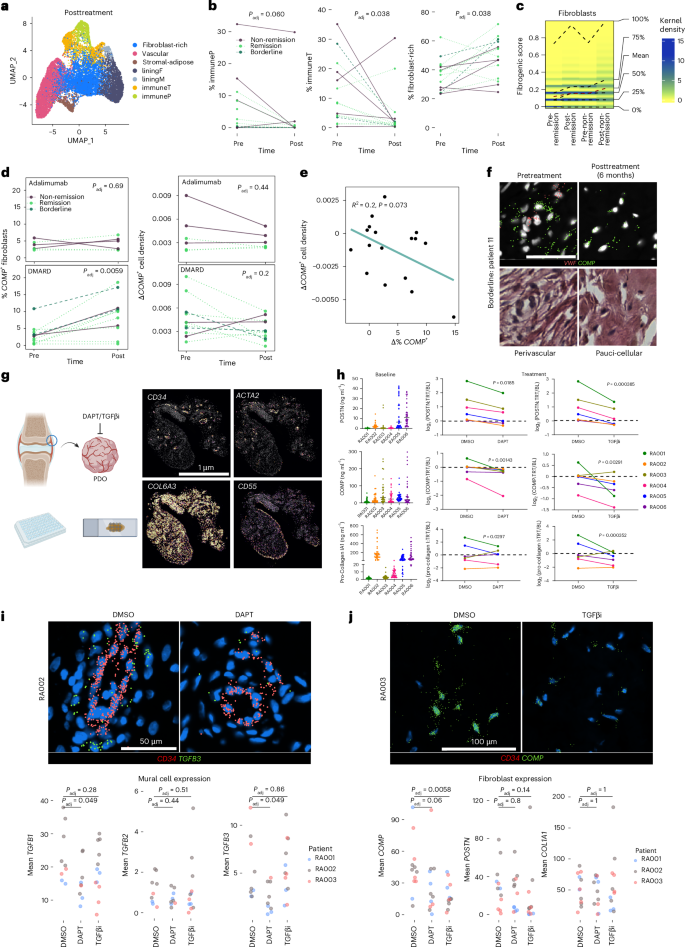

Posttreatment expansion of fibrogenic niches

Next, we evaluated the effect of treatment on fibrogenic signaling by analyzing 17 paired posttreatment synovial biopsy samples (Fig. 8a–c and Extended Data Fig. 8a–f). Across patients we observed substantial depletion of immune niches and immune subtypes and relative expansion of fibroblast-rich niches regardless of response status or treatment arm (Fig. 8b). Accordingly, tissue niche composition and swollen joint counts (SJC44, P = 0.2273) did not significantly differ between patients who achieved remission and those who did not (Extended Data Fig. 8f,g and Supplementary Table 1). However, while DAS28-ESR components decreased across remission groups, non-remission status was driven by significantly higher tender joint counts (TJC53, P = 0.0037) and VAS pain scores (P = 0.0233; Supplementary Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 8g).

a, UMAPs showing labeled posttreatment niche tiles. b, Quantification of the relative abundance of immune and fibroblast-rich niches before treatment and after treatment (n = 16 patients). Line colors indicate remission status. c, Density plot of fibrogenic UCell scores by time and remission status. Color gradient represents the density of cells expressing the indicated score, with dashed lines indicating percentile score distributions per biopsy category. d, Quantification of COMP+ fibroblast abundance and cell density before treatment and after treatment (n = 11 DMARD-treated, n = 6 adalimumab-treated). e, Correlation between changes in the percentage of fibroblasts that express COMP and the cell density of COMPhi regions per patient after 6 months of treatment. Statistics by two-sided Pearson correlation test. f, Representative COMP gene expression and paired H&E for a pretreatment and posttreatment biopsy from a borderline patient. VWF marks vasculature. Scale bar, 50 µm. g, Schematic summarizing the PDO experiments and representative transcript density plots for spatially profiled PDOs showing genes that highlight core synovial tissue structures. Scale bar, 1 µm. h, ELISA data showing supernatant levels of POSTN, COMP and PRO-COL1 in PDOs incubated overnight (left), alongside the median per-patient log2 fold change of these proteins after 3 days of treatment, normalized to overnight per-organoid protein production (n = 10–13 PDOs per condition). Statistics by Gaussian GLM, patient included as a cofactor, with FDR correction. i,j, Representative images of transcript expression in indicated conditions (top) and per-PDO average mural cell (i) and fibroblast (j) expression of indicated genes (bottom). In b, d, i and j, a two-sided Wilcoxon test was used.

Examination of fibrogenic gene expression in fibroblasts from posttreatment biopsy samples revealed elevation of the fibrogenic signature across groups (Fig. 8c and Extended Data Fig. 8h). Accordingly, we observed increases in the percentage of fibroblasts expressing COMP in most patients (remission/borderline, 5/10 patients; non-remission, 6/7 patients), with starker increases under DMARD treatment (Fig. 8d and Extended Data Fig. 8i). COMPhi tissue regions became more pauci-cellular after treatment, with an inverse relationship between COMP+ cell abundance and COMP+ cell density (Fig. 8d–f). These data suggest that after treatment, COMP-expressing fibroblasts expand and may deposit fibrous ECM. Over time, this process could generate pauci-cellular niches, thus supporting active fibrogenic remodeling in the fibroblast-rich compartment of RA following immune depletion.

Next, we evaluated whether serum markers could be used as surrogates to track fibrogenic activity in synovium by profiling pretreatment and posttreatment serum with an ~5,400-plex protein panel (Olink; Extended Data Fig. 9a,b). Neither individual fibrogenic proteins nor inflammatory markers showed significant trends by time point or remission group (Extended Data Fig. 9a). A number of stromal markers, including EGFL7 (r = 0.685), an endothelial-expressed angiogenic factor37, were highly correlated with the fibrogenic score or change in fibrogenic score, although they did not meet significance (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Therefore, we extended our analysis to the AMP cohort15 to identify which cell-type abundance (CTAP) phenotype was most associated with fibrogenic signaling (Extended Data Fig. 9c–f). Fibroblasts from the CTAP characterized by endothelial, fibroblast and myeloid cells (CTAP-EFM) were the most strongly enriched for the fibrogenic gene signature and COMP expression compared to fibroblasts from other CTAPs (Extended Data Fig. 9c). Interestingly, patients belonging to CTAP-EFM, on average, also had significantly longer disease duration (Extended Data Fig. 9d). We performed differential abundance analysis of serum proteins in CTAP-EFM patients (n = 7) versus those classified as belonging to other CTAPs (n = 60). In patients belonging to CTAP-EFM, we observed enrichment of several established fibrogenic markers including SPARC, OGN and CCN2 (Extended Data Fig. 9e,f). Collectively, these data support fibrogenic remodeling in a subset of patients with RA who have a longer disease duration and the potential to capture proteomic signatures at later stages of disease when joint activity may be reflected systemically38.

Finally, we evaluated the feasibility of targeting Notch and TGFβ signaling to diminish fibrogenesis in RA synovial tissue (Fig. 8g–j and Extended Data Fig. 10a–e). We obtained synovial tissue from patients with active RA (n = 6), generated >30 patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from each tissue with a 2-mm punch biopsy tool, and treated each PDO with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), DAPT or TGFβi for 72 h after overnight rest, collecting media after the initial overnight incubation to establish the baseline per-PDO fibrogenic protein secretion. Across RA donors, we observed relatively high and variable production of COMP, POSTN and PRO-COL1 (Fig. 8h). Treatment of RA PDOs with both DAPT and TGFβi resulted in a significant reduction of COMP, POSTN and PRO-COL1 (Fig. 8h and Extended Data Fig. 10a). We applied the custom fibrogenic gene panel to spatially profile PDOs from three RA donors (Fig. 8i,j and Extended Data Fig. 10b–f), identifying four distinct cellular niches based on marker gene expression: vascular, lining, sublining and mural (Fig. 8g and Extended Data Fig. 10b,c). There was evidence of immune activity, although the panel was not designed to detect these populations (Extended Data Fig. 10d). To determine the effect of DAPT on perivascular TGFβ isoform and receptor expression, we examined the EC-proximal mural cell compartment where Notch signaling was most enriched (Fig. 8i and Extended Data Fig. 10e). Consistent with our observations from in vitro-cultured fibroblasts, DAPT treatment significantly suppressed TGFB1 and TGFB3 expression while de-repressing TGFBR2 and TGFBR3. Further, per-organoid fibroblast COMP expression was significantly diminished by TGFβi and reduced with DAPT (Fig. 8j and Extended Data Fig. 10f). Spatially, COMP was most abundantly expressed in the pauci-cellular regions, where TGFβi most profoundly reversed gene expression (Fig. 8j). Collectively, our data suggest that therapeutic targeting of Notch or TGFβ signaling may abrogate fibrogenic signaling in RA synovia.