Presentation of study design (Fig S1), and full statistical analysis results (Table S3 + S4) can be found in supplementary materials.

General welfare and body weight changes following induction of monoarthritis

Overall, both types of joint injections and all volumes caused signs of inflammation (oedema, erythema, and heat detected by palpation) located to the area surrounding the injected joint, observed from 5 h post induction. However, none of the rats exceeded a cumulative welfare score of 0.4, which indicates a humane endpoint (Table S5).

Body-weight data was normalized to reflect a change from baseline, and a mixed-effects analysis showed significant effects of time for both sexes and injection-group across all datasets (Fig. 1, non-normalized data: Fig S2). Mixed-effects analysis also showed significant interactions between injection volume and time for ankle-injected males (P = 0.0016, Fig. 1A) and a trend in females (P = 0.06, Fig. 1B). This suggests that the ankle injections affected the rats’ usual growth curve, thus confirming earlier observations made in male rats only7. Area Under the Curve (AUC) analysis of D0-10 and analysis across sex, revealed significant effects of both sex and injection-group, but no direct correlation between the actual volume and weight gain in the studied period (Fig. 1C), which could suggest that the impairment in growth had already reached a maximum with the lower volumes.

Body weight (BW) % change from baseline following induction of ankle or knee monoarthritis (MA). Timeline changes in body weight following ankle-joint (AJ) injection of 10, 20 or 50 µl (AJ-10, AJ-20, AJ-50, respectively) was measured in (A) male and (B) female rats. (C) The change in body weight over time was transformed into an Area Under the Curve (AUC) from Baseline to Day 10 after injection and displayed as a “volume-response relationship”. There was no significant volume-response relationship in neither males nor females when including the non-injected control-group (black line) or the ankle-injected groups alone (dashed green line). Timeline changes in body weight following knee-joint (KJ) injection of 10, 50 or 100 µl was measured (KJ-10, KJ-50, KJ-100 respectively) in (D) male and (E) female rats. (F) The change in body weight over time was transformed into an AUC from Baseline to D10 and displayed as a “volume-response relationship”. There was a significant volume-response relationship in males and a mild trend in females when including the non-injected control-group (black line), but not when comparing knee-injected groups alone (dashed green line). All data is presented as mean ± SEM. Time-course data (fig A–B + D–E) were analysed by mixed-effects model analysis followed by Dunnett’s post comparisons tests with the control group (results in Supplementary Table S3). For the AUC figures (C + F); simple linear regression was assessed per sex to determine a volume-response relationship, and 2-way ANOVA determined overall effects across sex with Dunnett’s post-test comparison to sex-specific control, as symbolized by; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS = not significant. For all groups: N = 6 (baseline-Day 10), N = 4 (Day 13–15) and N = 2 (Day 20). BW = Body Weight, MA = Monoarthritis, AUC = Area Under the Curve, CTRL = Control.

Even more prominent findings were detected for the knee-injected groups, where there were either trending or significant effects of injection-group for males (P = 0.08, Fig. 1D) and females (P = 0.02, Fig. 1E), with significant time*group interactions for both sexes. The AUC analysis confirmed the significant effects of injection-group and sex. Correlation analysis for males showed a significant (P = 0.006) negative correlation between the volume injected into the knee and the weight gained (Fig. 1F), suggesting that the higher injection volumes were associated with less weight gain. We could not substantiate this association in females (P = 0.096), which may merely reflect a ceiling effect in the BW decrease for females already with the 50 µl volume. Analysis across joint, sex and injection volumes (3-way ANOVA) confirmed the significant effects of sex and injection-groups, but no effect of joint site or interactions, suggesting that the effects of the CFA-injections on decreased body-weight gain were not dependent on the joint location.

Changes in model-specific parameters following induction of monoarthritis

In general, the CFA-injection into the ankle or knee resulted in a similar transient, but pronounced, change of model-specific parameters during the first three days after induction (Fig. 2). As there were no clear sex-differences (Fig S3-4), the results are displayed across sex. As these scores are considered ordinal and descriptive (Table S6), they are presented as a percentage of the group receiving a given score, and with no statistical analysis.

Model-specific parameters were increased in male and female rats subjected to ankle or knee joint monoarthritis (MA). Following the injection of 10, 20 or 50 µl CFA into the ankle joint (AJ), or 10, 50 or 100 µl into the knee-joint (KJ), various model-specific parameters were assessed. Mobility (A and B), lameness (C and D), stance (E and F) and rearing (G and H) were assessed on scales ranging from 0–4, 0–3 or 0–2, and here presented as percentage of animals in each group on a given day, that received a given score. For all the parameters, the higher the value, the higher level of impairment of said parameter. The higher intensity of colour suggests a higher proportion of the group receiving the score in question. As there were no apparent sex differences, the data is presented across sex, but full sex-separated results are presented in supplementary figure S2-3. Animals were scored at 5 h (5 h), Day 1 (D1), 3 (D3), 10 (D10), 15 (D15) and 20 (D20) after model-induction. For all groups across sex: N = 12 (baseline-Day 10), N = 8 (Day 13–15) and N = 4 (Day 20).

Overall, regardless of injection volume and joint-location, animals scored higher on all model-specific parameters in the initial stages, and became progressively lower with time, suggesting that the CFA-induced impairment was most profound in the beginning, followed by a gradual recovery. For general mobility, no injection volume or site induced the two most severe scores (Fig. 2A-B). For the ankle-injected rats, half of the animals receiving the low volume (AJ-10) returned to normal on D15-20, while none receiving the higher volumes recovered fully (Fig. 2A). In contrast, for knee-injected animals, all in the low and medium volume groups returned to normal. Even half of the rats receiving the largest volume into the knee joint recovered full mobility by D20 (Fig. 2B).

The lameness score focused specifically on the use of the injured limb. While all injected animals, regardless of site and volume, reached the most severe score in the initial days, the overall development resembled the mobility score. No rats injected with medium or high volumes of CFA into the ankle recovered fully in the use of the affected limb (Fig. 2C). In contrast, knee-injected animals recovered better, with all low and medium volume, and half of the high-volume, animals recovering completely (Fig. 2D).

In the stance (Fig. 2E-F) and rearing (Fig. 2G-H) parameters, all animals fully recovered by D20. However, it was evident that greater volumes of CFA, injected into either joint, were associated with slower recoveries. Similarly, in the early post-induction phase (5 h-D1), a higher proportion of animals receiving the largest injection into the ankle received higher severity scores (Fig. 2E + G). For knee-injected rats, the different injection volumes affected these scores equally in the initial stages (Fig. 2F + H).

In summary across all parameters, bigger injection-volumes caused a greater proportion of animals to receive more severe scores for an extended duration. In addition, following the knee-injection model a higher proportion of animals achieved full recovery on parameters related to especially mobility and lameness compared to ankle-injected animals. This suggests a greater and more prolonged impact from the ankle-injection model on these parameters.

Changes in joint circumference following induction of monoarthritis

Next, joint circumference was measured as a proxy for the level of inflammation associated with joint injection. Data was normalized to pre-injection baseline to evaluate the level of inflammation as an increase in circumference (non-transformed: Fig. S5). Mixed-effects analysis showed significant effects of injection-group, time and a time*injection-group interaction following ankle injection in both males (Fig. 3A) and females (Fig. 3B). This interaction suggest that the swelling behaved differently over time, depending on the injection volume that was used. Post-test comparison at the individual timepoints showed that all ankle-injected animals were significantly different from control at all timepoints after injection. AUC-conversion detected no significant sex-differences, but clear effects of injection-group (2-way ANOVA). Correlation analysis showed a significant association between the injection volume and the resulting circumference-increase, although the correlation was weak (males) or non-significant (females) if the control groups were excluded (Fig. 3C). We suspect that this is due to a ceiling effect, where the female rats’ joint swelling reached a maximum already with a CFA-volume of 10 µl.

Joint circumference (%) was increased in the injected joint following induction of monoarthritis (MA) in the left ankle or knee joint in male and female rats. Timeline development of inflammation following ankle joint (AJ) injection of 10, 20 or 50 µl CFA (AJ-10, AJ-20, AJ-50, respectively), was assessed by measuring ankle circumference, and normalized to present an increase from baseline, in (A) males and (B) females. (C) The development of ankle inflammation over time was transformed into an Area Under the Curve (AUC) from Baseline to Day 10 and displayed as a “volume-response relationship”. There was a significant volume-response relationship in both males and females when including the non-injected control-group (black line), but not for females when comparing ankle-injected groups alone (dashed green line). Timeline development of inflammation following knee-joint (KJ) injection of 10, 50 or 100 µl CFA (KJ-10, KJ-50, KJ-100 respectively), was assessed by looking at knee circumference, normalized to baseline, in (D) males and (E) females. (F) The development of knee inflammation over time was transformed into an AUC from Baseline to Day 10 and displayed as a “volume-response relationship”. There was a significant volume-response relationship in both males and females both when including the non-injected control group (black line), and when comparing knee-injected groups alone (dashed green line). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. Time-course data (fig A–B + D–E) was analysed by mixed-effects model analysis followed by Dunnett’s post comparisons tests with the control group. For the AUC figures (C + F); simple linear regression was assessed per sex to determine volume-response relationship, and 2-way ANOVA determined overall effects across sex with Tukey’s post-test comparison between groups. Comparison to sex-specific control; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Low volume group; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, +++p < 0.001, Medium volume; ##p < 0.01. For all groups: N = 6 (baseline-Day 10), N = 4 (Day 13–15) and N = 2 (Day 20). MA = Monoarthritis, AUC = Area Under the Curve, CTRL = Control.

Similar findings were seen for the knee-injected groups, where statistical analysis showed significant effects of time, injection-group, and interaction of the two factors for both male (Fig. 3D) and female (Fig. 3E) rats. Post-test comparison suggested that the effects decreased with time, particularly for females, as only the high-volume groups produced significantly increased circumferences at D6-8, while no groups were different from controls at D10-20. AUC-conversion showed significant effects of both sex and injection-group, as there was more swelling in males than females, but overall, a clearly increased inflammation with increasing volume for both sexes (Fig. 3F). This was also confirmed by linear regression, detecting a significant volume-response relationship in both sexes following knee injection (Fig. 3F).

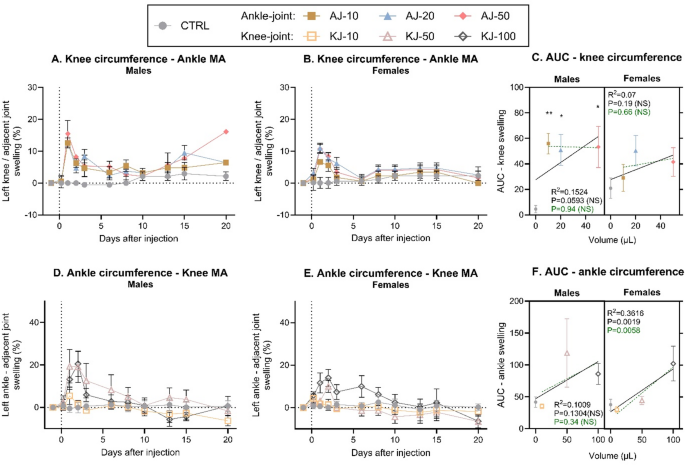

The circumference of the adjacent ankle or knee joint was also evaluated to investigate potential spread of inflammation from the injected joint. The circumference was again normalised to pre-injection baseline (Fig. 4, non-normalised: Fig S6). CFA-injection into the ankle resulted in a significant increase in circumference of the adjacent knee joint, in males (Fig. 4A) but not females (P = 0.10, Fig. 4B). For both sexes there were significant effects of both time and a time*injection-group interaction, suggesting that the effect of the ankle injection on secondary spread to the knee, was dependent on time, as the most prominent swelling was seen in the beginning of the test phase. AUC-conversion showed significant effects of injection-group, and an almost significant volume-response relationship in males (Linear regression, P = 0.059), but only when the control-group was included in the correlation (Fig. 4C). This suggests that all ankle-injection volumes caused spread of inflammation to the knee-joint, and that the spread was not worsened with increasing doses.

A subsequent increase of circumference (%) was detected in adjacent ipsilateral joints after induction of knee- or ankle monoarthritis (MA). Time-line development of inflammation in the knee-joint following CFA-injection of 10, 20 or 50 µl into the ankle joint (AJ), was assessed by measuring knee-circumference, normalized to present a percent increase from baseline in (A) male and (B) female rats. (C) The development of knee-inflammation over time was transformed into an Area Under the Curve (AUC) from Baseline to Day 10, and displayed in a “volume-response relationship”. There was an almost significant volume-response relationship in males, but not females, when including the non-injected control-group (black line), but for neither when comparing ankle-injected groups alone (dashed green line). Timeline development of inflammation in the ankle-joint following CFA-injection of 10, 50 or 100 µl into the knee joint (KJ), was assessed by measuring ankle circumference normalized to baseline, in (D) males and (E) females. (F) The development of ankle-inflammation over time was transformed into an AUC from Baseline to Day 10, and displayed in a “volume-response relationship”. There was a significant volume-response relationship in females, but not males, both when including the non-injected control-group (black line), and when comparing knee-injected groups alone (dashed green line). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. Time-course data (fig A–B + D–E) was analysed by mixed-effects model analysis followed by Dunnett’s post comparisons tests with the control group. For the AUC figures (C + F); simple linear regression was assessed pr sex to determine volume-response relationship, and 2way ANOVA (sex*injection-group) determined overall effects across sex with Tukey’s post-test comparison between groups. Comparison to sex-specific control suggested by; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; between other groups; NS. For all groups: N = 6 (baseline-Day 10), N = 4 (Day 13–15) and N = 2 (Day 20). MA = Monoarthritis, AUC = Area Under the Curve, CTRL = Control, NS = Not Significant.

Similar findings were detected when measuring the ankle-joint in animals subjected to CFA-injection into the knee. Here, there were significant effects of time, and an interaction between injection-group and time, suggesting that the injection had different effects during the study-period (Fig. 4D + E). Post-test comparison clarified that the spread from knee to ankle joint was most prominent in the early phase as only the high injection volumes was different from control from D1-2 for males and D1-6 for females. Also, for the knee injections, the AUC conversion showed significant effects of injection-group, and for females a significant correlation between the injection volume and degree of circumference in the adjacent ankle joint (Fig. 4F).

In summary, it appears that CFA ankle injection results in a maximum level of inflammation/swelling with as little as 10 µl, both for inflammation in the injected and adjacent joints. This inflammation is maintained for a prolonged period, particularly at the primary site. Contrarily, for knee injections, there are clear volume-dependent effects with more prominent levels of inflammation as the volume is increased. Notably, it seems the inflammation improves earlier when injecting into the knee compared to ankle.

Changes in dynamic weight bearing (DWB) following induction of monoarthritis

Dynamic weight bearing was used as a measure of the compensatory redistribution of weight bearing away from the affected leg, serving as an indirect measure of pain associated with load on the injured joint16. Statistical analysis showed clear effects of time, injection-group and a time*group-interaction for both males (Fig. 5A) and females (Fig. 5B) exposed to ankle-injection. Particularly the early phase was characterised by an almost complete depletion in weight bearing on the ipsilateral leg for all animals given ankle injections of any volume. For both sexes, all ankle injection volumes produced a significant decrease in weight bearing on the injected leg at all timepoints, except at D20. The AUCs confirmed an effect of injection-group, and that all ankle injected groups were significantly different from control (Fig. 5C). There was a significant volume-dependent relationship, only when the control group was included in the analysis, due to the almost full depletion in ipsilateral weight bearing for all injected groups in the early phase of the experiment.

Dynamic weight bearing (DWB) (%BW) on the left (ipsilateral) hindlimb was decreased after induction of ankle or knee monoarthritis (MA). Timeline development of weight bearing deficits following ankle joint (AJ) injection of 10, 20 or 50 µl CFA (AJ-10, AJ-20, AJ-50, respectively), was assessed by looking at the proportion of bodyweight carried on the ipsilateral leg in (A) males and (B) females. (C) The development of weight bearing deficits over time was transformed into an Area Under the Curve (AUC) from Baseline to Day 10 and displayed as a “volume-response relationship”. There was a significant volume-response relationship in both males and females when including the non-injected control group (black line), but not when comparing ankle-injected groups (dashed green line). Timeline development of weight bearing deficits following knee joint (KJ) injection of 10, 50 or 100 µl CFA (KJ-10, KJ-50, KJ-100 respectively), was assessed by looking at the proportion of bodyweight carried on the ipsilateral leg in (D) males and (E) females. (F) The development of weight bearing deficits over time was transformed into an AUC from Baseline to Day 10 and displayed as a “volume-response relationship”. There was a significant volume-response relationship in both males and females when including the non-injected control group (black line), but not when comparing ankle-injected groups (dashed green line). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. Time-course data (fig A–B + D–E) was analysed by mixed-effects model analysis followed by Dunnett’s post–comparisons tests with the control group. For the AUC figures (C + F); simple linear regression was assessed per sex to determine volume-response relationship, and 2-way ANOVA determined overall effects across sex with Dunnett’s post-test comparison to sex-specific control, as symbolized by; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. For all groups: N = 6 (baseline-Day 10), N = 4 (Day 13–15) and N = 2 (Day 20). MA = Monoarthritis, AUC = Area Under the Curve, CTRL = Control, NS = Not Significant.

Similarly, the knee-injection produced significant effects of time, injection-group and interaction on DWB, for both males (Fig. 5D) and females (Fig. 5E). All knee-injected animals showed significantly decreased weight bearing across the experiment, except on D20 (males) or D15-20 (females) for the low volume groups. The AUCs confirmed significant effects of injection-groups, and that all injected groups were significantly different from control (Fig. 5F). Analysis of the AUC also showed a significant volume-dependent relationship, only when the control-group was included, due to the almost full depletion in weight bearing on the injected limb for all injected groups, in the early phase of the experiment.

For both ankle and knee injection models, these findings suggest that, particularly in the early phases, even the lowest injection volumes almost completely abolish load bearing on the affected limb, with no additional effect of increasing volumes. Across joint injection sites, sex, and volumes, a 3-way ANOVA of the AUC (from Fig. 5C + F) showed significant effects of injection-group, but no effect of sex, joint, or any interactions. This suggests that for the tested volumes, both ankle and knee injections induced similar weight bearing deficits in both sexes. As expected, the decrease in weight bearing on the affected limb led to significantly increased weight bearing on the right (contralateral) hind limb (Fig S7) and secondarily on the front legs (Fig S8). The pattern in how the weight was redistributed was overall similar across sex, joints-location and injection-volumes.

Open field test (OFT) & sucrose preference test (SPT)

Locomotor activity measured by distance travelled in an OFT was assessed one and 14 days after CFA injection. On D1 (Fig. 6A), there were significant effects of injection-group and sex, as females were generally more active, but there was no sex*injection-group interaction, suggesting that the injection-groups affected the sexes equally. Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test clarified that across sex, AJ-10, AJ-20 and KJ-100 displayed significantly shorter distance travelled than control animals (P < 0.05), suggesting a reduction in locomotor activity. On D14 (Fig. 6B), there was no effect of injury-group (P = 0.90), but still a significant effect of sex, as females still displayed higher locomotor activity.

Locomotion, anxiety- and depressive-like changes after induction of monoarthritis (MA). Locomotor activity was assessed as distance travelled during 15 min in an Open Field (OFT) at (A) Day 1 and (B) Day 14 after CFA-injection into the ankle (AJ) or knee joint (KJ) for males (M) and females (F). Anxiety-like behaviour was assessed as time spent in the center of the OFT on (C) Day 1 and (D) Day 14 after induction of CFA-injection. Differences between MA groups were analysed by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, as suggested by *P < 0.05. For all groups: D1: N = 6 and D14: N = 4. D = day. E) Sucrose intake was measured in the home cage during 2 * 24 h at pre-injury baseline (Base), Days 0–2 (acute phase) and Days 13–15 (chronic phase), and presented with both sexes combined. Differences were analyzed by a mixed-effects model analysis followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for comparison to group-specific baselines. For all groups, both sexes combined: N = 6 (baseline-Day 10) and N = 4 (Day 13–15). For all panels; Data are presented as mean ± SEM. CTRL = Control.

Time spent in the center of the OFT arena was measured to assess anxiety-like behaviour at one (Fig. 6C) and 14 (Fig. 6D) days after injury. Two-way ANOVAs showed no effects of injection-group, but a significant effect of sex, as males spent overall more time in the center. This suggests that the CFA injections did not induce anxiety-like behaviour.

The sucrose preference test was used to assess depressive-like behaviour, specifically anhedonia. As the outcome was measured in the animals’ home cage, and rats were pair-housed with a cage-mate from the same experimental group, the home cage was considered the experimental unit. After initially confirming that there was no significant effect of sex on the outcome, males and females were combined for each injection group (Fig. 6E, sex-separated dataset; Fig S9). A repeated-measures mixed-effects model detected significant effects of time, suggesting that the preference for sweet consumption changed during the experiment. Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test showed that the proportion of sweet consumption was significantly decreased in the first 2 days after injury for one ankle- (AJ-20) and all knee-injected groups, when compared with the specific groups’ baseline measures. In the late phase, sweet consumption had normalised again. This suggests that, particularly the knee-injection model, produced acute but transient depressive-like behaviour.

Histopathological changes following induction of monoarthritis

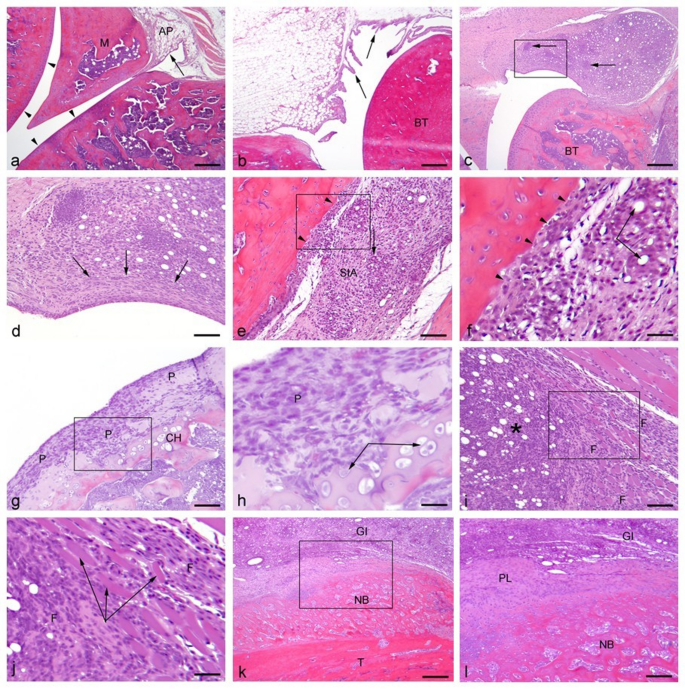

As previously5, histopathological changes are presented in a descriptive manner, with examples of histological findings presented in Fig. 7. Uninjured control examples of knee and ankle-joints are presented in Fig. 7a-b respectively, while pathological changes are shown in Fig c-l with examples from sections obtained from the low volume groups. Independent of injection volume and timepoint, successful induction of chronic arthritis was achieved, and the lower volumes did not decrease the pathological characteristics of the model. Prominent features identifiable within all groups were lipid-droplet-containing (CFA remnants) granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 7.c-f), consisting primarily of macrophages and occasional multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 7.e), and granulation tissue comprised of proliferating fibroblasts and newly formed vessels, markedly expanding the synovium and often completely replacing the adipose tissue (Fig. 7.c-f). Across all groups, cartilage and bone destruction, substituted by layers of pannus (Fig. 7.g-h), could be identified. Periarticular leakage of CFA-remnant, causing a granulomatous inflammation intermingling atrophic muscle fibres, was also often present (Fig. 7.i-j). Furthermore, periosteal bone formation was identified among all groups, with new bone formation being especially notable among ankle-injected rats (Fig. 7.k-l).

Histopathological changes. HE-stained sagittal sections of ankle and knee joints. All sections are from animals inoculated with 10 µl CFA and euthanized on day 10. (a) Knee, normal. The synovial membrane is lined with a thin layer of cells (arrow), and within the sub-intima, adipose tissue (AP) is present. The articular surfaces are lined by uniform cartilage (arrowheads). M = meniscus. Bar: 600 μm. (b) Ankle, normal. The synovial lining consists of 1–3 layers of synovicytes (arrows). Intact, uniform cartilage is present on joint surfaces overlying normal bone tissue (BT). Bar: 600 μm. (c) Knee. The sub-intimal area is heavily infiltrated by mononuclear cells (macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells) (arrows), forming granulomas around lipid droplets of CFA. The articular surfaces and underlaying bone tissue (BT) are unaffected. Bar: 600 μm. (d) Close-up of the synovial lining in (c). Widespread granulomatous inflammation within the sub-intimal area is intermingled with CFA lipid droplets, and fibrosis is present (arrows). Bar: 150 μm. (e) Ankle. Widespread granulomatous inflammation, with occasional giant cells (arrow), within the sub-intimal area (SIA) is intermingled with CFA lipid droplets. Pannus-formation is seen along the articular surface, and the cartilage is destructed (arrowheads). Bar: 150 μm. (f) Close-up of (e). Lipid droplets contained by macrophages and multinucleated giant cells (arrows). Pannus has substituted the cartilage lining (arrowhead). Bar: 75 μm. (g) Knee. Due to pannus-formation (P), the cartilage lining and underlying bone tissue are destructed with reactive chondroid hyperplasia (CH). Bar: 150 μm. (h) Close-up of (g). Proliferating chondrocytes (arrows). P = pannus Bar: 75 μm. (i) Knee. Periarticularly, granulomatous inflammation with CFA lipid droplets (*) has caused intramuscular fibrosis (F). Bar: 150 μm. (j) Close-up of (i). Intramuscular fibrosis (F) accompanied by muscular atrophy (arrows). Bar: 75 μm. (k) Ankle. Granulomatous inflammation (GI) with CFA lipid droplets present along the tibia (T), on which extensive new periosteal bone formation is present (NB). Bar: 600 μm. (l) Close-up of (k). The new bone formation is formed by endochondral ossification from the periosteal lining (PL) overlined by granulomatous inflammation (GI). NB: new bone formation. Bar: 150 μm.

As suggested by the spread of joint-swelling to adjacent joints, high-volume groups (AJ-50 and KJ-100) showed histological changes in ipsilateral adjacent joints (ankle to knee, and knee to ankle) as well, suggesting that with higher volumes, there was an increased spread outside of the intended joint site. AJ-50 showed an impact on the knee joint more frequently than KJ-100 to the ankle joint.

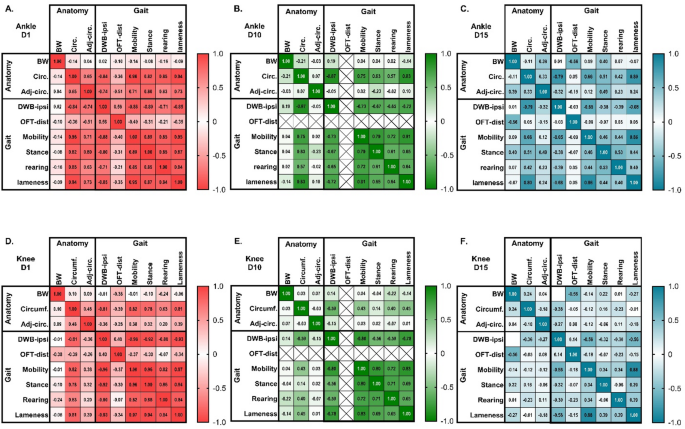

Correlations between outcomes affected by monoarthrits induction

Finally, the connection between the different outcomes was assessed, to explore if, for instance, a high degree of inflammation was associated with higher degree of changes in other outcomes. To do this, correlation matrices for the different timepoints were created, including all the outcome measures performed on the given day in the same animals (Fig. 8 + S10). As some outcomes, like circumference, was affected by the anatomical joint location, the matrices were made per joint, but including all injection groups, controls and sexes in each matrix. On D1, there were clear correlations between all outcome measures for the ankle-injured groups, with the only exception of body weight increase not correlating with any other measure (Fig. 8A). This clearly suggest that the higher the degree of ankle inflammation/circumference, the bigger the degree of spread to the adjacent joint, and the bigger the degree of changes in weight bearing, distance travelled and model-specific parameters. The same overall picture was seen on D3, with only the exception that the blunted body weight increase now significantly correlated with the degree of inflammation (joint circumference), weight-bearing deficits and model-specific parameters, suggesting that BW changes were delayed, but directly correlated with the severity of effects on the other parameters (Fig S10A). Ten (Fig. 8B) and 15 (Fig. 8C) days after injury, the correlations had subsided for the adjacent joint inflammation, body weight and distance travelled in the Open Field as these parameters returned to normal. Inflammation of the injected joint remained correlated with weight bearing and model-specific parameters. On D20, the degree of ankle inflammation was still correlated with weight-bearing deficits, mobility and lameness scores (Fig S10B).

The correlation between different outcome measures decreases over time after induction of monoarthritis in the ankle or knee joint. Correlations between experimental parameters were assessed in a correlation matrix for each individual timepoint and injection type, but across sex and injection volumes. Parameters were classified as related to “anatomy”: joint circumference increase (circ.), adjacent joint circumference increase (Adj-circ.), body weight increase (BW), or to “gait”: Dynamic Weight Bearing, ipsilateral limb (DWB-ipsi), Open Field Distance (OFT-dist) or the model-specific parameters (mobility, stance, rearing, lameness). (A–C) Presents Pearson correlation coefficients for ankle-injected groups on Day 1 (A), Day 10 (B) and Day 15 (C) after injection of 10, 20 or 50 µl of CFA into the ankle joint. (D–F) Presents Pearson correlation coefficients for knee-injected groups on Day 1 (D), Day 10 (E) and Day 15 (F) after injection of 10, 50, 100 µl of CFA into the knee joint. The more intense colours suggest a greater connection between two parameters (greater Pearson correlation coefficient), and significance levels are presented in detail in Supplementary Table S3. Crosses suggests that the parameters could not be compared, as OFT was not measured at that timepoint.

For the knee-injured groups, the immediate acute phase showed significant correlations that were like what was seen for the ankle-injected groups, with clear correlations between almost all parameters, besides bodyweight, on D1 (Fig. 8D), and including a blunted bodyweight increase on D3 (Fig S10C). In contrast to the ankle-injected animals, from D3 and onwards, no parameters correlated with the degree of inflammation in the adjacent joint. Like ankle-injured animals, the correlations remained between degree of inflammation of the injected joint, weight bearing and model-specific parameters for the knee-injured animals on D10 (Fig. 8E). The correlations were, however, overall weaker for the inflammation outcome compared to the ankle-injured animals. This was even more apparent at the later stages, where the degree of knee inflammation (measured as joint circumference) only showed a weak (D15, Fig. 8F) or non-significant correlation (D20, Fig S10D) with DWB, and with no (D15) or few (D20) other parameters.

Overall, for both injury locations, the connections between parameters grew weaker with time. But, for the knee-injured groups, most correlations between parameters became weaker or disappeared earlier than for the ankle-injured groups. Overall, this suggests a disconnect between the severity of the different parameters in the later stages. Particularly for the knee injection, some outcomes may improve before others, and particularly the level of inflammation measured externally of the joint-site, may be less reflective of the pain-related behaviour in the later stages of the knee injury, while more useful in ankle injuries.