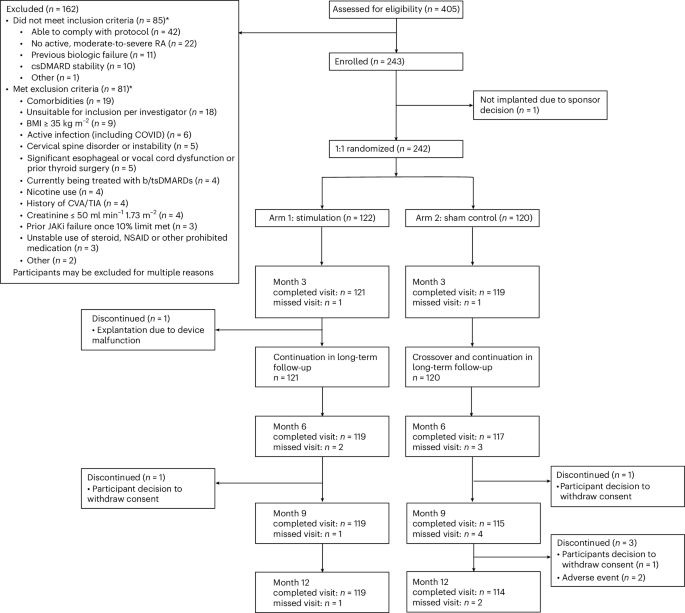

Patient disposition

Following approval by the institutional review board (Advarra centrally and three local boards), a total of 405 patients diagnosed with RA were screened for study participation, 243 were consented and enrolled, and 242 completed standard b/tsDMARD washout per protocol requirements before device implantation (intent-to-treat (ITT) population). Figure 1 provides patient disposition from screening through 12 months. Patients were randomized to either arm 1 (stimulation treatment for 3 months, then continued to open-label stimulation; 122 patients) or arm 2 (sham treatment for 3 months, then crossover to open-label stimulation; 120 patients) following postsurgical recovery. One consented patient was discontinued from the study before device implantation for logistical reasons; the patient was not randomized but was followed for safety per protocol. A single patient randomized to arm 1 did not continue in the study after the 3-month primary end point. The demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients at baseline are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–3. Overall, mean duration of RA was 12.4 years, and the mean (s.d.) and median (range) number of prior b/tsDMARDs was 2.6 (1.9) and 2.0 (1–12), respectively. The total number of patients (% overall population) who had prior exposure to 1 b/tsDMARD was 94 (38.8%), those exposed to >1 b/tsDMARDs was 148 (61.2%), those exposed to ≥3 b/tsDMARDs were 95 (39.3%) and to a tsDMARD were 49 (20.2%). At the time of consent, 78.5% of patients were taking stable doses of a single csDMARD, of which 51.1% were receiving methotrexate. The remainder received at least two csDMARDs. Open-label data are reported through 12 months; 233 patients from the ITT population completed the 12-month visit.

Patient disposition through month 12. BMI, body mass index; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack; JAKi, Janus kinaseinhibitor, NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Treatment

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-conditional pulse generator, the ‘implant’, was implanted and fitted within a contoured silicone pod that was secured directly to the left cervical vagus nerve15 (Fig. 2). Once implanted, targeted electrical pulses were delivered to the vagus nerve to engage the inflammatory reflex and modulate immune activity. The stimulation parameters were controlled by site-specific programmers using a tablet-based software application that transmitted information through a charger worn by the patient (Fig. 2). Those patients randomized to sham stimulation always received 0 mA, regardless of the stimulation strength set by the programmers, who were blinded to treatment arm assignment.

The integrated neuromodulation system consists of an implant and pod. The implant is placed in the pod to position and hold it in place on the left cervical vagus nerve to ensure direct contact for precise stimulation. The implant is approximately 2.5 cm in length and weighs 2.6 g. To charge the implant, patients wear a wireless device (charger) around the neck for a few minutes, once a week. The implant is programmed by healthcare providers (HCPs) using a proprietary application (programmer). Adapted from ref. 16, by permission of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

The active stimulation intensity was set to an upper comfort level (maximum = 2.5 mA) and delivered a 1-min train of pulses to the vagus nerve once daily at 10 Hz16 (arm 1 = 1.8 mA average; arm 2 = 0 mA). The 3-month assessments were completed for 99.2% of patients, with two missed visits (one in each arm). Supplementary medications that were prohibited per protocol before the 3-month assessment (‘rescue’) occurred in four patients in arm 1, and five patients in arm 2. All patients, healthcare providers, investigators, joint evaluators and the sponsor were blinded to group assignment until all patients completed assessments at 3 months and the database was locked for primary efficacy analysis.

Following the primary end point assessment at 3 months, all patients were eligible to continue in the study for open-label active stimulation treatment. Adjunctive pharmacological treatments (‘augmented therapy’) were permitted throughout the open-label stimulation period at the discretion of the rheumatologist in consultation with the patient, with 17.8%, 24.8% and 32.2% of patients receiving protocol-defined augmented therapy at 6, 9 and 12 months, respectively. At these timepoints, 88.0%, 80.6% and 75.2% of patients remained free from adjunctive b/tsDMARD therapy. During the open-label stimulation period, 96.3% of patients in the ITT population completed 12-month assessments.

Primary outcome

The primary end point was a difference in proportion of patients in the ITT population receiving stimulation versus sham who achieved an ACR20 response at the 3-month visit from baseline (day of consent). ACR20 response, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology, is a dichotomous composite end point representing the proportion of patients who achieve at least a 20% improvement in both the tender and swollen joint counts (out of a maximum of 28 joints) and in ≥3 of the following 5 additional measures—Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) score, patient global assessment of disease, patient pain, evaluator’s global assessment of disease and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentration17. The primary end point was met at 3 months; ACR20 response was achieved by 35.2% of arm 1 (stimulation) and by 24.2% of arm 2 (sham; Fig. 3a). The stratification-adjusted difference in ACR20 response between arms was 11.8% (P = 0.0209, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.6, 23.1). At 3 months, Bang’s blinding index scores were <0.3 for patients, joint assessors and co-investigators, which indicated satisfactory blinding at the time of primary end point assessment (Supplementary Table 4).

a, The percentage of patients who had an ACR20 response at 3 months, the primary efficacy end point of this study. Patients with missing data or who received rescue treatment were imputed as nonresponders. Stimulation, n = 122; sham, n = 120. b, The percentage of patients who had an ACR20 response through 12 months. Within double-blind period; stimulation, n = 122; sham, n = 120. At 6, 9 and 12 months, n = 97, 89, 77 in arm 1, respectively, and n = 98, 87, 81 in arm 2, respectively. c, The percentage of patients who had a DAS28-CRP good or moderate response according to the EULAR criteria. At 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, n = 118, 95, 85, 75 in arm 1, respectively, and n = 117, 98, 82, 79 in arm 2, respectively. d, The percentage of patients who had achieved LDA or remission by DAS28-CRP criteria (score < 3.2). At 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, n = 118, 95, 85, 75 in arm 1, respectively, and n = 117, 98, 82, 79 in arm 2, respectively. All data are presented as the percentage of each group with s.e. Formal statistical analyses were only performed at the 3-month study visit (double-blind) with the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test using stratification factors based on prespecified criteria (prior inadequate or lost response to a tsDMARD, prior inadequate or lost response to ≥4 biological DMARDs with ≥2 mechanisms of action and RA disease severity defined as either <4 TJC28 or <4 SJC28 at day 0), at a one-sided significance level of 0.025. P = 0.0209, 95% CI = 0.6–23.1 (a,b). P = 0.0048, 95% CI = 7.3–31.7 (c). P = 0.0154, 95% CI = 1.2–21.6 (d). After 3 months (open-label stimulation), patients were permitted to augment therapy with adjunctive drugs without restriction. Data presented at 6, 9 and 12 months in b–d include all patients completing the visit who had not used augmented therapy. Percent of patients with augmented therapy—6 months = 17.8%, 9 months = 24.8%, 12 months = 32.2%. BL, baseline. *P < 0.025, **P < 0.01.

Secondary outcomes

Four key secondary end points were evaluated, each representing the difference in the proportion of patients in the ITT population receiving stimulation versus sham who achieved the end point at 3 months. End points included a DAS28-CRP good/moderate response according to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria; a DAS28-CRP minimal clinically important difference (MCID; −1.2); a HAQ-DI MCID (−0.22); and an ACR20 response from day 0 (randomization). Among the key secondary end points, multiplicity adjustment was performed using Hochberg’s step-up procedure. All secondary end points showed a higher response rate for stimulation compared to sham, although significance was achieved for only EULAR good/moderate response (Supplementary Table 5). EULAR good/moderate response was achieved by 60.7% of arm 1 (stimulation) and by 41.7% of arm 2 (sham) (multiplicity-adjusted P = 0.0048, 95% CI = 7.3, 31.7). DAS28-CRP MCID was achieved by 45.1% of arm 1 and by 32.5% of arm 2 (multiplicity-adjusted P = 0.0528, 95% CI = 1.1, 25.3). HAQ-DI MCID was achieved by 45.9% of arm 1 and by 36.7% of arm 2 (multiplicity-adjusted P = 0.0797, 95% CI = −3.3, 21.4). ACR20 from day 0 was achieved by 31.1% of arm 1 and by 22.5% of arm 2 (multiplicity-adjusted P = 0.0797, 95% CI = 1.1, 25.3).

Exploratory outcomes

All other efficacy end points at 3 months and within the open-label stimulation period were exploratory. Open-label stimulation was initiated in both arms after the 3-month controlled-blind period. Response rates for primary and all secondary end points increased further in arm 1, while patients in arm 2 demonstrated clinical improvements following initiation of stimulation. Clinical end point responses were sustained in both arms through 12 months (Supplementary Table 5).

Clinically relevant composite measures

Prespecified clinically relevant composite outcome measures included EULAR good/moderate response, low disease activity (LDA) or remission by DAS28-CRP, and LDA or remission by the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) evaluated at 3 months (sham-controlled-blinded period) and also during the open-label stimulation period at 6 months, 9 months and 12 months (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Table 6). Arm 1 (stimulated) had significantly higher rates than arm 2 (sham) at 3 months for EULAR good/moderate response (% responders ± s.e.m.—arm 1 = 60.7% ± 4, arm 2 = 41.7% ± 5; P = 0.0048, 95% CI = 7.3, 31.7) and DAS28-CRP LDA/remission (% rate ± s.e.m.—arm 1 = 26.1% ± 4, arm 2 = 15.4% ± 3; P = 0.0154, 95% CI = 1.2, 21.6). Difference in rates for CDAI LDA/remission at 3 months did not reach significance (% rate ± s.e.m.—arm 1 = 23.3% ± 4, arm 2 = 16.0% ± 3; P = 0.0648, 95% CI = −2.1, 17.7), although favored stimulation.

All composite outcome measures improved further in both arms during the open-label period, when all patients received stimulation, with responses maintained at 12 months. Across both arms, the percentage of patients who achieved an ACR20 response at 12 months was 57.6%, EULAR good/moderate response was 77.3%, DAS28-CRP LDA/remission was 44.8%, and CDAI LDA/remission was 43.9% by a nonaugmented analysis (Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Table 6). Comparable results were observed by an all-completers analysis, which additionally included those patients who received augmented therapy (Supplementary Table 6). Patient satisfaction rate using a five-point Likert rating scale revealed that 78.1% of patients were somewhat to very satisfied with the therapy at 6 months (satisfaction %—arm 1 = 75.6%, arm 2 = 80.7%; Supplementary Table 10).

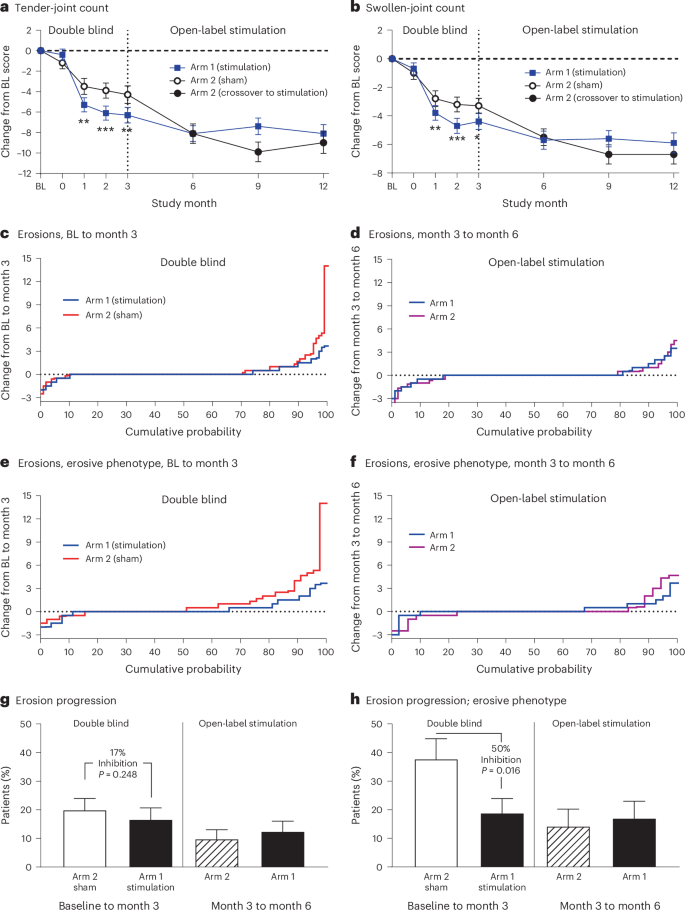

Outcome Measures in Rheumatology RA MRI score

Treatment effects on joint inflammation and erosions were assessed using gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the hand and wrist at baseline (pre-implant), 3 months and 6 months. Images were analyzed with the validated Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) RA MRI score (RAMRIS) to objectively quantify bone erosion progression18. In the ITT population, a total of 216 patients had RAMRIS scores measured at both baseline and 3 months (arm 1, n = 109; arm 2, n = 107). At baseline, bone erosion scores were comparable between arm 1 and arm 2, with a mean (s.d.) erosion score of 10.4 (11.7) and 9.5 (12.1), respectively. From baseline to 3 months, a smaller proportion of patients in arm 1 (stimulation) exhibited progression of bone erosions (>0.5 increase in score) in the evaluated hand and wrist compared with arm 2, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.248; Fig. 4c,g). In the prespecified subgroup analysis of patients with a phenotype enriched for erosive damage risk (defined as synovitis score of 2 or more on any individual joint, at least four joints with a score of 1 or any joint with osteitis at baseline), a total of 105 patients met the erosive phenotype criteria (arm 1, n = 57; arm 2, n = 48). In this subgroup, the rate of progression of bone erosion from baseline to 3 months was significantly decreased in arm 1 (stimulation = 18.9%) as compared with arm 2 (sham = 37.8%, P = 0.016; Fig. 4e,h). During the open-label stimulation period from 3 months to 6 months, the rate of progression of bone erosion declined in arm 2 (Fig. 4g,h).

a,b, The mean change and s.e. in the number of tender and swollen joints and as compared to baseline are shown in a (tender-joint count) and in b (swollen-joint count). The vertical line at 3 months indicates the end of the double-blind period of the study and the beginning of open-label stimulation. For a and b, within double-blind period: stimulation, n = 116; sham, n = 114. At 6, 9 and 12 months, n = 96, 88 and 77 in arm 1, respectively, and n = 98, 87 and 80 in arm 2, respectively. c–f, The cumulative probability of a change in erosion score, as assessed via the OMERACT RAMRIS. The right part of the curve (positive values on the y axis) represents erosion progression (worsening), the left part of the curve represents erosion regression (improvement) and the flat line at y = 0 represents no change in erosion score. c,e, Plot change from baseline to 3 months during the controlled-blind period. d,f, Plot change from 3 months to 6 months during open-label stimulation. Patients who completed the 3-month and 6-month visits without augmented therapy are included in c and d. Patients at risk for erosion progression are included in e and f. g,h, The percentage of patients who had erosion progression, defined as >0.5 increase in RAMRIS erosion score by MRI. The vertical line at 3 months demarcates the double-blind period between baseline and 3 months and the open-label stimulation period between 3 months and 6 months. Data are presented as the mean (a,b) or the percentage of each group (g,h) with s.e. Statistical analyses were only performed at points through 3 months; a and b with mixed-effect model repeated measures and g and h with the CMH test. All tests use one-sided significance level of 0.025. In a, P = 0.0021, 0.0004 and 0.0014 at month 1, 2 and 3, respectively. In b, P = 0.0097, 0.0009 and 0.0131 at month 1, 2 and 3, respectively. *P < 0.025, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Sensitivity analyses

Primary and secondary end point response measures during the open-label period were consistent with analyses using nonresponder imputation to account for missed visits or study dropouts (Supplementary Table 5). At 12 months from baseline, ACR20 response by nonresponder imputation were 50.4% (61/121) and 51.7% (62/120) for arm 1 and arm 2, respectively; EULAR good/moderate response was 70.2% (85/121) and 70.8% (85/120) for arm 1 and arm 2, respectively; DAS28-CRP MCID was 60.3% (73/121) and 55.8% (67/120) for arm 1 and arm 2, respectively; and HAQ-DI MCID was 54.5% (66/121) and 55.8% (67/120) for arm 1 and arm 2, respectively.

Safety

The safety evaluation was based on all available data at the time of reporting, with a mean implant duration of >700 days. No deaths or unanticipated adverse device effects occurred at any point during the trial. Overall, adverse events occurred in a similar proportion of patients in both arms during the controlled period (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 11). Nonserious related adverse events were predominantly associated with the implantation procedure (Supplementary Table 13), reported in 38 patients (15.6%; 52 events). These were consistent with those seen in other devices implanted near the cervical vagus nerve. The most frequent events were mild to moderate hoarseness, classified as either vocal cord paresis (4.5%, n = 11) or dysphonia (2.9%, n = 7). These adverse events resolved over the course of up to one year; three patients received bulk injection fillers into the left vocal cord and some underwent voice therapy. No cases required surgical intervention. Additional implantation-related adverse events of mild to moderate severity occurred in 5.4% of patients related to the surgical site (n = 13), including swelling/inflammation (n = 6), hypoesthesia (n = 2), stitch abscess/infection (n = 2), pain (n = 1), erythema (n = 1) and a suture-related complication (n = 1). Active stimulation (1 min daily) was generally well tolerated. Mild to moderate stimulation-related events, most commonly pain, occurred in 4.2% of patients (n = 10) during the controlled period and 4.6% (n = 11) during long-term follow-up. These typically resolved after reducing stimulation strength or adjusting the time of delivery, without interruption of therapy.

Overall, during the controlled period and long-term follow-up, 4 of 242 ITT patients (1.7%) experienced a serious adverse event related to surgical procedure, all having an onset during the perioperative period (1.6% of the 243 enrolled patients in the safety population). All these events resolved without clinically significant sequelae. There was one event of postoperative incision-site swelling, one event of transient vocal cord paresis (presented as hoarseness) with dysphagia, one intraoperative pharyngeal perforation (that occurred during an explantation procedure and was immediately repaired) and one event of postoperative dysphonia (that presented as hoarseness) possibly associated with postoperative progression of age-related vocal cord bowing (presbylarynges; Table 2). There were no serious adverse events related to the active stimulation.

A total of six patients underwent device removal (explantation) before 12 months. All explantations were performed as outpatient, elective procedures. The reasons for explantation included a nonfunctioning device (n = 1), chronic pain at the incision site (n = 1), gastrointestinal symptoms attributed to stimulation therapy (n = 1) and patients who requested removal due to perceived lack of benefit (n = 3). During the explantation procedure, the vagus nerve appeared to be normal on visual inspection.

Details of the safety results during the open-label stimulation period are provided in Table 2 and Supplementary Tables 17–21. No safety concerns have been identified through other protocolized safety monitoring assessments (for example, vital signs, hematology, ECG, blood pressure, heart rate). All adverse events of infection, major adverse cardiac events and malignancies were reviewed and determined to be unrelated, and the rates were within the expected range for the target RA patient population.